|

|

From the Archive

007 Issue #13 (1983) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Moving on to You

Only Live Twice (1967). Up to that time all outer space SFX were

compared to Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Were

you aware that you were going to encounter problems of comparison between

your SFX and those in 2001?

Of course you could never hope to duplicate the SFX of 2001 because

of the limited time and money at your disposal. No, we didn’t give it a

thought really. What we did was pretty current; whereas 2001 was

supposed to be set 2001. We used techniques and hardware that was

contemporary at the time. In fact one of the ideas we had for doing the

interception (subsequently changed in the final film) NASA hadn’t thought

of, and they have developed it since then. I still have long talks with

NASA about things.

I believe the sequence involving the helicopter flight over the

volcanoes contained a degree of model work, together with

Wing Commander

Ken Wallis’ ‘Little Nellie’.

Yes, I’m still very great friends with Ken. In fact I’ll be seeing him

shortly. |

|

|

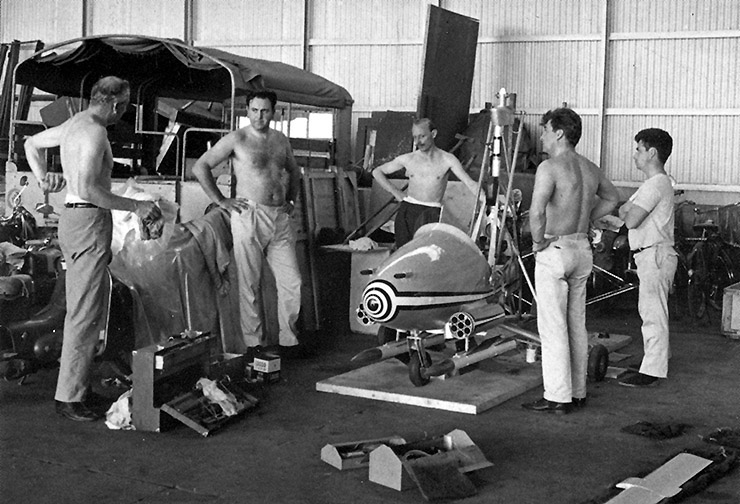

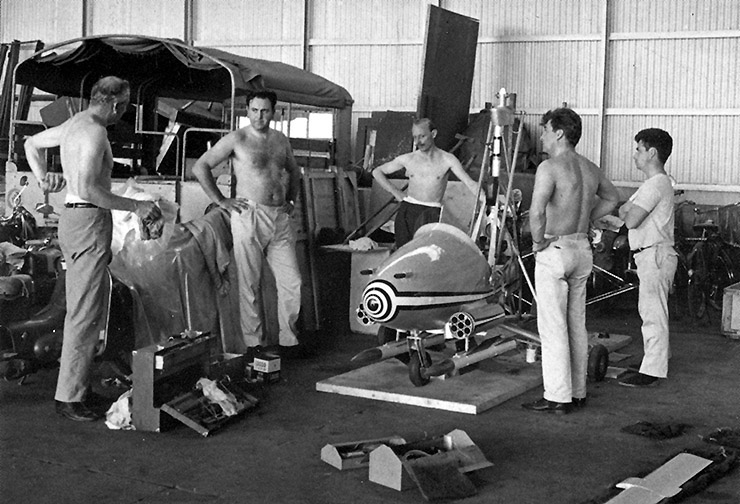

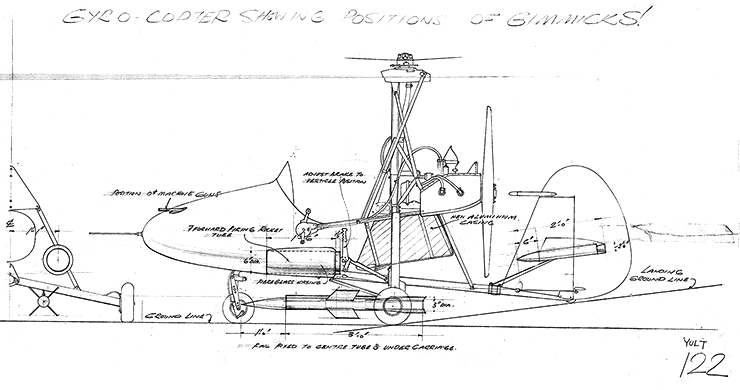

ABOVE: [L-R] Wing

Commander Ken Wallis (designer and pilot of ‘Little Nellie’), John

Stears, Bert Luxford, Joe Fitt and an unidentified technician

assemble the Wallis WA-116 autogyro in Japan ready for filming on

You Only Live Twice (1967). |

|

|

|

How much of the gadgetry was real on ‘Little Nellie’?

Nearly all the rockets were real, and the sidewinders – only the

machineguns were pyrotechnic FX, and certainly ‘Little Nellie’ could fly

with all those gadgets for real. But before her missiles could be fired in

actual flight I had to carry out a significant number of calculations and

tests. I had visited Ken at his workshop at Reymerston Hall where we had a

long discussion about how exactly we could attach all the missiles and

gadgets to his autogyro. There were a lot of factors to be considered,

like none of the additions should get in the way of the landing gear;

affect the slipstream of the aircraft or the aircraft weight. Being an

aircraft buff myself, Ken and I worked extremely well together from the

word go. Incidentally, Ken also made all the components for his flying

machines himself, being not only an accomplished pilot but also a superb

engineer. His workshop was an Aladdin’s cave!

Everything I need to do

the job had to be handmade. Nothing existed from stock! The missiles were

a problem, inasmuch they had to fire in a straight line ahead of the

autogyro, which would be doing around 120 knots. The missiles had to have

the power to accelerate away from Little Nellie’s flight line, and also

there had to be no chance of the aircraft catching the missiles or them

turning back to hit her. I was not concerned about the cluster missiles as

they were a known ballistic, and I had used the Icarus rockets before with

various types of exploding payloads of my own making. But the two long

air-to-air missiles were an unknown factor. I had to devise them from

scratch. My problem was, they had to be lightweight and stable in flight –

not an easy combination to achieve. I made a drawing and had Ken check it

out to see if the autogyro could handle two of them in the position

indicated in my drawing. |

|

|

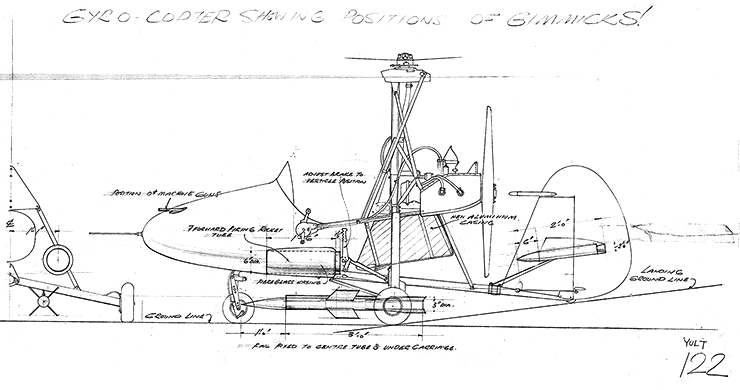

ABOVE: (left) ‘Little Nellie’ on location in Japan and (right) on

set back at Pinewood Studios. BELOW: A production drawing by

Michael White showing John Stears’ modifications to ‘Little

Nellie’. |

|

|

|

|

Getting the okay from

Ken, Bert Luxford (part of my SFX team) went ahead and made our prototype,

which when completed gave me the exact weight factor necessary to

calculate how much thrust I needed to get direction, speed and stability

required. I was looking for a one-to one thrust weight ratio or better,

with duration of at least eight seconds burn time. There was no time to

develop a rocket motor myself so I had to use what was available. The only

choice was Shermuly’s Line Throwing Rocket, which provided around seven

pounds of thrust. I could arrange four of these in the tail of the

missile, which gave me 28lbs of static thrust. The missile with the rocket

weighed approximately the same.

Now the moment of truth. Did I have enough power? Did I have the centre of

gravity correct? How straight would it fly – if at all? Bert had built a

launching ramp and installed it on the roof of the art department building

at Pinewood Studios. I remember it was after lunch. The day was grey with an

overcast sky. There was no wind. Perfect for a first firing. Other SFX

team members Jimmy Ackland-Snow

(1905-1975) and Joe Fitt (1924-2002) were also there to watch. We

were facing toward the end of Black Park’s pine trees – which run the

perimeter of the studios’ fence – so if the rocket overshot the lot it

would get stopped in the trees, which were wet, and wouldn’t cause a

problem. |

|

|

ABOVE: One of the

models built by John Stears’ team for the aerial battle between

SPECTRE and ‘Little Nellie’ in You Only Live Twice (1967).

|

|

|

|

There was some set construction going on to the right of us, well out of

our line of fire, and in shouting distance. Everything was ready. I called

out to the riggers on the set being constructed, ‘Fire in the hole!’ They

acknowledged, ‘OK John!’ Ten, nine, eight, seven, six, five, four, three,

two, one – fire! I pressed the ignition button. The missile paused for a

moment – then off it went! No problems, perfectly straight, no wobbles, as

if designed by NASA! It was flying exactly where it was supposed. The burn

time was perfect the motor stopped. But instead of the missile nosing over

and coming down, it stayed exactly the same height and made a perfect

right turn through 180 degrees then straightened out – coming back toward

us at 150 mph! One problem was, the construction crew were in the way –

and they couldn’t see it coming. We all yelled out for them to take cover

and get out of the way. I don’t know where I thought they could go – they

were on scaffolding! As luck would have it the missile sailed past them

about 30 feet away and landed at the bottom of the building we had

launched it from!

I heard the construction crew talking later, discussing how clever the

effect boys were, ‘They even make their own guided missiles!’ If only

they’d realised. |

|

|

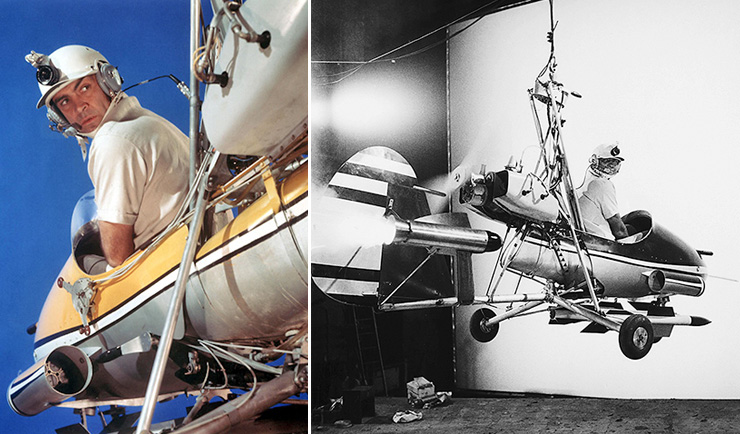

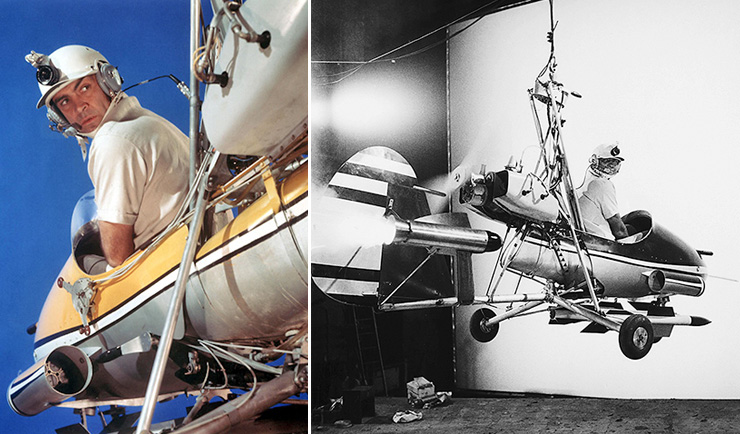

ABOVE: For the shots

showing Sean Connery flying ‘Little Nellie’, the actor was filmed

against a blue-screen with the autogyro suspended in the studio

and intercut with the footage captured in Japan and Spain with the aircraft

flown by Wing Commander Ken Wallis. The aerial footage was filmed

by cameraman

Johnny

Jordan who had a foot sliced off by rotor blades from one of

the SPECTRE helicopters, which then crashed into to the mountain

side. Although Jordan’s foot was reattached, it was so badly

damaged he decided to have it amputated and replaced with a

prosthetic tin leg. Jordan returned to film the spectacular aerial

sequences in On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969), which

were mostly achieved with him suspended in a special rig beneath a

helicopter that allowed him an unbroken 360-degree field of

vision. Whilst acting as Second Unit director on Catch-22

(1970), John Jordan was killed when he fell out of an aircraft as

it banked without warning – he’d uncoupled his safety harness to

get a better shot! |

|

|

|

I imagine the Ninja

attack on Blofeld’s volcano headquarters in You Only Live Twice

must have entailed very detailed preparation?

Yes. I mean this is where Bond started getting really extravagant in terms

of sets and things, and you couldn’t really control things as much as you

wanted to because, although I was in Japan on location, I had to leave

pretty early to come back and set up the volcano shot, so you’re leaving

things with other people, you can’t avoid it, but one would have thought

it better if we could have had more time. But it was a time when returns

on investment had to be fast, labour rates were sky-high and we had to cut

corners on time.

And of course with 2nd and 3rd units filming different sections,

presumably there wasn’t the close communication that was a part of the

earlier films?

Well, it started getting difficult.

You worked for Harry

Saltzman on a film called Toomorrow (1970), which I believe was

only screened once and then withdrawn due to a legal argument. But it was

supposed to have had quite brilliant SFX in the sci-fi style?

Well it was a bit like E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982) really,

although we didn’t have an ET like E.T. I think actor Roy Dotrice

played the part, but yes there were good FX. |

|

|

How big was the model of Piz Gloria in On Her Majesty’s Secret

Service (1969)?

I’m not sure, not too big, about the size of this room, I think about 1:48

scale.

Were any of the helicopters in the attack on Piz Gloria sequence

models?

Yes, for certain scenes.

Were they more complex than the model used in From Russia With Love?

No, the same thing. |

|

|

|

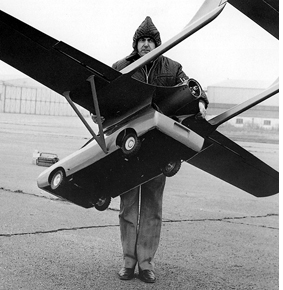

ABOVE: Scaramanga's

(Christopher Lee) flying car was achieved via the combination of

using a miniature and a modified AMC Matador Coupe, which had

wings and a propeller attached (centre left). The radio-controlled

miniature is seen in The Man With The Golden Gun (1974) as

the car takes off after Scaramanga out manoeuvres James Bond

(Roger Moore), who is chasing in a red AMC Hornet. The full-size

AMC Matador was displayed at the 1974 Earl's Court Motor Show

(bottom right) with John Stears receiving a credit on the car for

its design, and he also attended the Motor Show. |

|

|

|

Moving to The Man

With The Golden Gun (1974), the final James Bond film you worked on –

what was your biggest problem on that picture?

The biggest problem was with the aircraft. The problem was I was working

with a full-sized aircraft and I was basing everything on the power I

could fly the model with, and I was given the specification of an American

jet engine that would do the job, and they were two months late delivering

the engine. And when it did finally arrive there were so many problems

with it, it just wasn’t on. It was a prototype, and I had to change

everything at the last minute and we just got away with it. The power we

eventually had was so marginal for the type of aircraft that if the

barometric pressure was high I couldn’t get it off the ground, but if it

was too low, i.e. a stormy day, I would get uplift and I could fly it – so

we just got away with it!

You’ve just finished working on The Hound of the Baskervilles

(1983). What FX did you supply for that production?

Well, backups on the dogs. We had six hounds of various sorts, but it’s

not our picture, we were just asked to go in and help with the hounds.

Now that you are freelance and have your own company you must get a lot of

offers for different projects. What makes you choose one film in

preference to another?

Oh well, I’ve been doing this now for nearly 30 years and I don’t want to

know if there are going to be problems with the crew, an inexperienced

crew, or insufficient money on the table or not enough time. But I’m in

the situation now where I’ve really got to do my own picture – there’s no

question about that. I’ve been involved in making movies for other people

for so long that I’ve got the opportunity now and that’s going to happen

next year (1983), we start shooting around about June. |

|

|

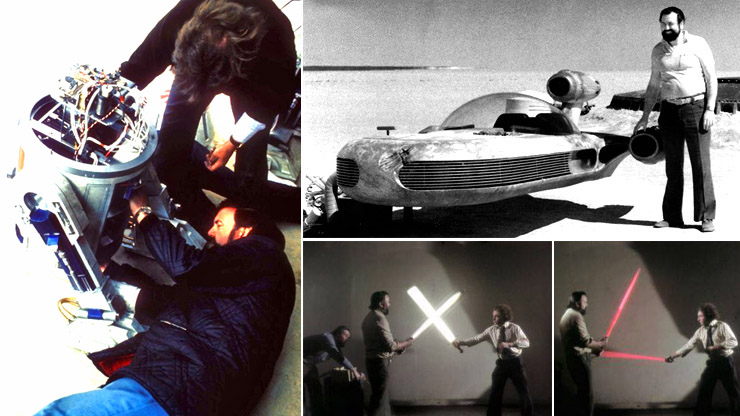

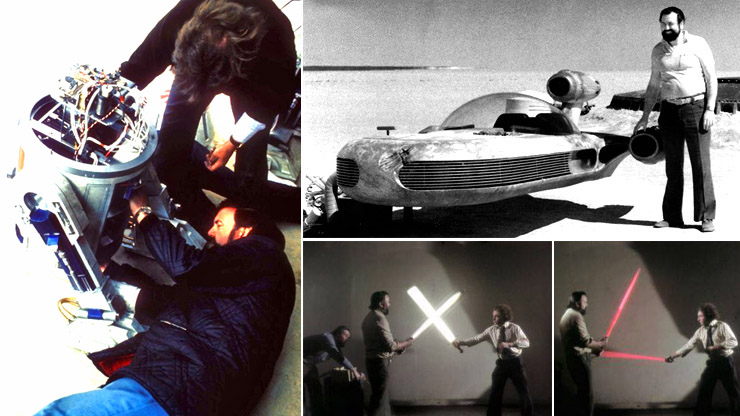

ABOVE: ‘A long time

ago in a galaxy far, far away...’ John Stears’ work on Star

Wars (1977) would win him a second Academy Award (shared with

the team from Industrial Light and Magic), and a Saturn Award

(shared with John Dykstra). John's work on Star Wars was

predominantly on the practical on-screen effects - such as a

radio-controlled R2-D2 (left), Luke Skywalker's land-speeder (top

right), and early tests for the light-sabres (bottom right). John Stears would also be nominated for a Saturn award in 1982 for his

work on Outland (1981) starring Sean Connery.

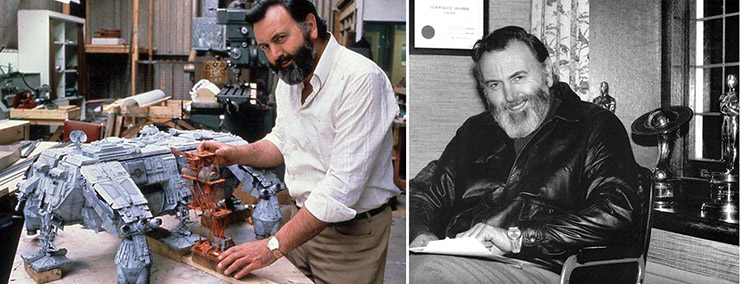

BELOW: Special Effects Wizard John Stears with one of his

highly-detailed Outland (1981) models, and (right) at home

with his Saturn Award and two Oscars. |

|

|

|

|

Is the film going to be in the Star Wars mould?

Well, it’s going to be entirely different – but you’ll just have to wait

and see.

In your career you’ve worked with American SFX technicians and American

film crews – is there any difference in the way each other work?

No. They learn from us (laughs). No, joking apart, they got involved with

the computerised camera, which works extremely well and all credit to

them, but on the physical effects side, they had that gap when they went

into TV and learnt from us. In fact I was in Hollywood recently and they

are still behind us. Their pictures are still coming here for the FX.

With the success of films like Star Wars (1977) and the general feeling

that the British are the best SFX technicians in the world, it seems

strange there is still this reluctance to invest British money in films?

Well, I think I may be able to reverse that.

I take it you’ve got around that problem with your upcoming film?

Yes, that’s right, it has totally British backing. But on this question of

backing, I think you could get more British money in films – but of course

the biggest problem is, unless you have a hit in the States the film will

be a flop financially. And how do you get your film on screens in the

States because American investment controls the theatrical circuits. |

|

|

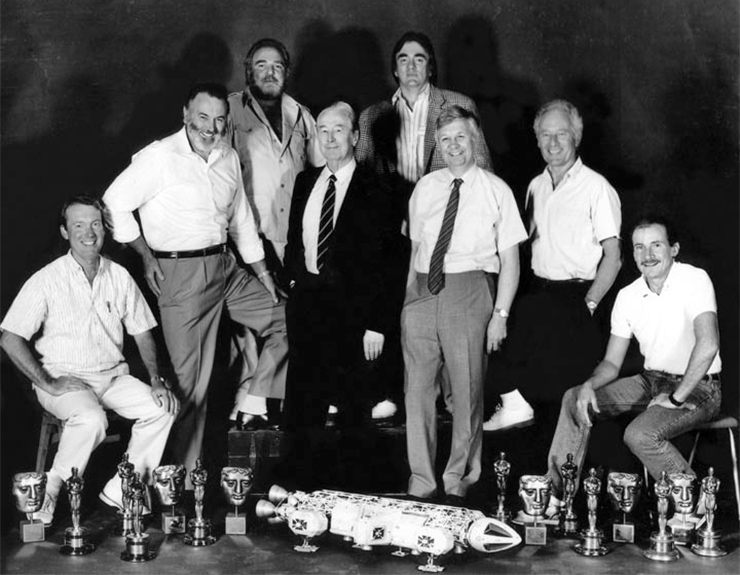

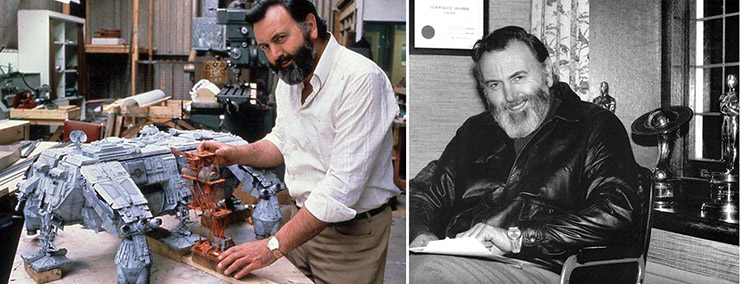

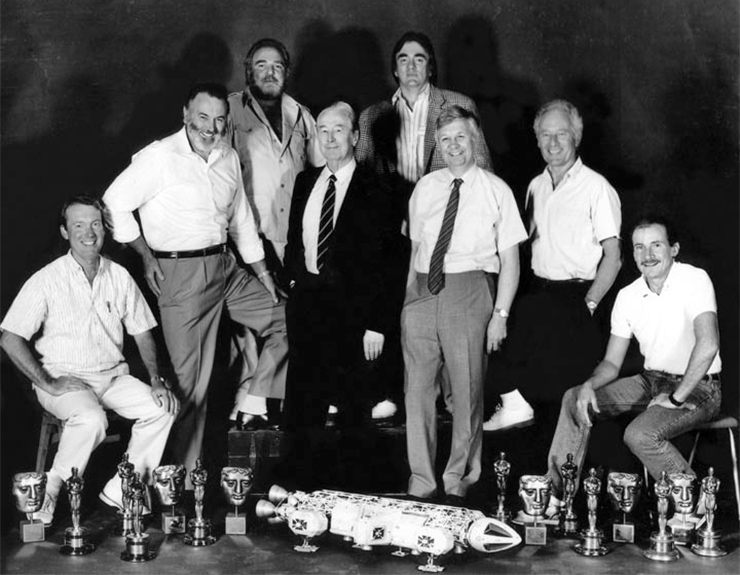

ABOVE: A WINNING

TEAM! - After leaving the James Bond series in 1974, John Stears worked on the British science-fiction television

programme Space 1999 - devised by Gerry & Sylvia Anderson,

which ran for two series from 1975 to 1977. Among the other

talented technicians working on the series were three other Bond

film alumni, and multi award-winning special effects creators.

[L-R] George Gibbs (1937-2020) [Indiana Jones

And The Temple of

Doom (1984), Brazil (1985), Who Framed Roger Rabbit

(1988)]; John Stears; Kit West (1936-2016) [Raiders

Of The Lost

Ark (1981), Return Of The Jedi (1983)],

Charles Staffell (1915-1999) [Dr.

No (1962), From Russia With Love (1963), Goldfinger

(1964), Thunderball (1965), You Only Live Twice (1967), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), On Her Majesty's Secret Service

(1969),

Diamonds Are Forever (1971), Live And Let Die (1973), Superman (1978),

Octopussy (1983), A View To A Kill (1985), Aliens

(1986)]; Brian Johnson (1940- ) [Alien (1979), The Empire Strikes

Back (1980), Aliens (1986)];

Roy Field (1932-2002) [Dr.

No (1962), From Russia With Love (1963), Goldfinger

(1964), Thunderball (1965), You Only Live Twice

(1967), On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969), Diamonds

Are Forever (1971), The Man With The Golden Gun (1974),

The Omen (1976), Superman (1978)];

Derek Meddings

(1931-1995) [Live And Let Die (1973), The Man With The

Golden Gun (1974), The Spy Who Loved Me (1977), Superman

(1978), Moonraker (1979), For Your Eyes Only (1981),

Batman (1989), GoldenEye (1995)];

Richard Conway

(1942-2021) [Indiana Jones And The Temple of Doom (1984),

Brazil (1985), Little Shop Of Horrors (1986)]. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Due to recent U.S.

import tariffs and significant increases in UK Royal Mail

charges, we are unable to supply 007 MAGAZINE to customers

in the United States at this time. |

|

|

|

|

|

|