| |

27 November 2006 |

Never Say McClory Again!

|

|

|

GRAHAM RYE takes a look at the life and times of Kevin McClory (1926-2006) To the general reader

the name Kevin McClory, who died aged 80 on November 20th, will strike no

chord, but to most devotees of James Bond history the name will be forever

associated with the Ian Fleming novel, film and THUNDERBALL trial - and

his myriad aborted attempts countered by countless litigation to launch an

alternative James Bond film franchise from highly questionable rights! |

|

|

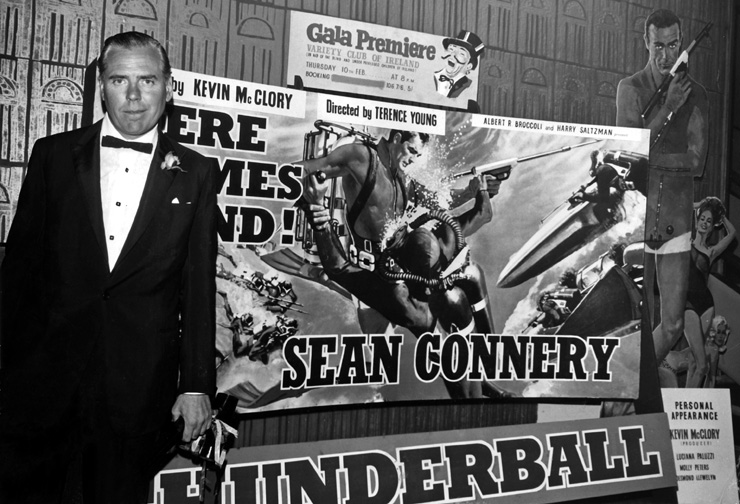

ABOVE: Kevin McClory at the Dublin premiere of Thunderball

(1965) held at the Savoy cinema on February 10, 1966. |

|

|

|

Born in Dublin on June

8th 1926, Kevin O’Donovan McClory was a descendent of the Bronte sisters,

by his grandmother Alice McClory. His parents were both actors on the

Irish stage, which fired his early desire to become an actor, but this

ambition was hampered by severe dyslexia at school, and was finally

blocked by a nervous stammer that was caused by a traumatic incident in

World War II; in 1943 when serving in the Merchant Navy McClory’s ship was

torpedoed while in the North Atlantic. He drifted over 700 miles in a

lifeboat in freezing conditions with other crew members for 14 days,

before being picked up off the coast of Ireland as one of the few

remaining survivors.

In 1946, his desire still strong to be in showbusiness and now with a

greater appreciation of life, McClory talked his way into £4-a-week job as

a boom operator and directors’ ‘tea boy’ at Shepperton Studios. With a

burning ambition to be noticed McClory worked in various capacities on

classic British films including Anna Karenina (1948) and The

Cockleshell Heroes (1955). It was during this early period at

Shepperton that he formed a life-long friendship with director John

Huston, another larger-than-life Irishman. McClory would eventually become

Huston’s assistant on pictures like The African Queen (1951) and

Moulin Rouge (1952), before graduating to Assistant Director on

Huston’s version of the Herman Melville classic Moby Dick (1956)

starring Gregory Peck. This proved McClory’s stepping stone to become

jack-of-all trades on the mammoth production Around The World In 80

Days (1956), with him acting as producer Mike Todd’s assistant,

Assistant Producer, and Assistant Director. |

|

|

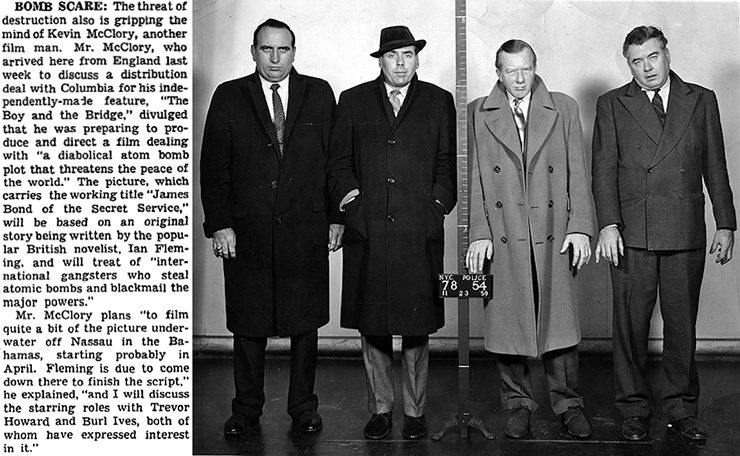

ABOVE: (left) New York Times report from November 15, 1959

announcing the production of ‘James Bond of the Secret Service’

co-authored with Ian Fleming. (right) A week later whilst still in

New York, Kevin McClory playfully arranged to have his friends

arrested, and they posed for a joke photograph. Pictured above

[L-R] are Lieutenant Kelly of the New York police, McClory,

screenwriter Jack Whittingham, and production manager & producer

Leigh Aman. |

|

|

|

McClory wanted more control over his own creative destiny and decided to

write, produce and direct The Boy And The Bridge (1959). Blarney

continued to baffle brains when McClory met wealthy Englishman Ivar Bryce

in The Bahamas. Bryce formed Xanadu Productions with McClory to finance

his first solo production. Bryce was a very close friend of James Bond

author Ian Fleming, and it wasn’t long before, at Bryce’s suggestion, that

McClory read several of Fleming’s novels with a view to filming one of

them. The young super enthusiastic Irishman soon realised that these books

had great potential. And great earning potential! However, McClory thought

very much in visual terms, a hangover from his childhood dyslexia, and

believed that he, Fleming and Bryce should collaborate on an original more

cinematic screenplay. To this triumvirate on behalf of Xanadu Productions

he introduced Jack Whittingham, then ranked among the Top 10 screenwriters

in the UK, whose work had been received with great critical and public

acclaim in Ealing Studios films including Mandy (1952) and The

Divided Heart (1954), who wrote a first draft screenplay that

eventually Ian Fleming would title Thunderball. The Bondwagon was

about to start rolling, the big bucks and the fame were only a stone’s

throw away, or so McClory believed. Unfortunately for him, The Boy And

The Bridge performed very badly at the world box-office and sank

without a trace. Bryce and Fleming’s initial enthusiasm for the young

Irishman handling the production of their first James Bond film project

suddenly faded. Expecting the profits from The Boy And The Bridge

to part-finance the Thunderball film both Bryce and Fleming got

cold feet and walked away from the project leaving McClory high and dry.

Neither men had been particularly up front in their dealings with McClory,

and it was only a matter of time before the Force Majeure would hit the

fan! |

|

|

ABOVE: (left) Kevin

McClory is presented to HRH Princess Margaret at the Royal

Premiere of The Boy And The Bridge held at the Curzon

cinema on Shaftesbury Avenue in London's West End on Wednesday

July 22, 1959. (right) A London Trolleybus displaying double-crown

posters advertising The Boy And The Bridge (1959) which

played at the Curzon cinema until Thursday August 20, 1959. The

Boy And The Bridge was chosen as the UK entry at the 1959

Venice Film Festival (August 23 – September 6, 1959) where it was

nominated for the Golden Lion award as Best Film. |

|

|

|

When Ian Fleming sat at his typewriter at his Jamaican home ‘Goldeneye’ in

January 1961 to write his ninth Bond novel he was in ill-health with heart

trouble and felt very much a spent force. Writing to William Plomer, an

old friend from his days with Naval Intelligence, who always proof-read

and pre-edited his Bond novels, Fleming complained that he was,

“Terribly stuck with James Bond. What was easy at 40 is very difficult at

50. I used to believe – sufficiently – in Bonds and blondes and bombs. Now

the keys creak as I type and I fear the zest may have gone. Part of the

trouble is having a wife and child. They knock the ruthlessness out of

one. I shall definitely kill off Bond with my next book – better a poor

bang than a rich whimper!” Perhaps it was no surprise then that a

tired writer would turn to a convenient formed idea. Why let it go to

waste? So Fleming based his ninth novel THUNDERBALL on the collaborative

screenplay without any idea of including any credit for McClory’s input

and Whittingham’s screen treatment. It would prove to be a costly error in

judgement. Or was it the act of a man who knew his life was coming to a

close and didn’t care? Or just arrogance? |

|

|

ABOVE (left) A

humiliated Ian Fleming leaves the High Court followed by his

friend and co-defendant Ivar Bryce. (right) A victorious Kevin

McClory leaves the High Court accompanied by his wife “Bobo” Sigrist, Jack Whittingham, and screen actor and friend Peter

O'Toole. |

|

|

|

Prior to the publication of THUNDERBALL on March 27th 1961 in London by

Jonathan Cape, Kevin McClory obtained an advance proof copy of the novel.

As soon as he realised that Fleming had plagiarised their collaborative

screenplay he sent a warning letter to the publishers that if they

published the book as it stood he would take legal action. Receiving no

answer from publishers Jonathan Cape, McClory sued. McClory was out to

stop Jonathan Cape from publishing THUNDERBALL representing it as the sole

work of Fleming. At a hearing a judge decided that since the accused had

insufficient time to mount a defence and publication of THUNDERBALL was

already so well advanced it couldn’t be stopped, McClory and Whittingham’s

application was refused. A little over two weeks after the failed book

injunction, Ian Fleming suffered a major heart attack during the regular

Tuesday morning conference at The Sunday Times. He was rushed to

The London Clinic where he remained for a month.

The ensuing case that began on November 20th 1963 at the High Court in

London was heavily covered in the media. Newspaper headlines screamed

‘JAMES BOND IN A ‘THUNDERBALL’ CLASH!’ Jack Whittingham found it necessary

to withdraw as co-plaintiff due to escalating costs, but, although in

extreme ill-health, returned every day to loyally support McClory, who

ultimately would do nothing to help Whittingham meet his crippling court

costs. After nine days in court both Ivar Bryce and Ian Fleming decided to

settle. McClory’s settlement demand? £55,000.

In the final outcome Kevin McClory was awarded £35,000 and his court costs

paid (totalling £52,000), plus the film and TV rights to all the existing

Thunderball screen treatments. However, even though he had won the

case he was unhappy with the financial result and never paid his lawyer’s

costs.

Ian Fleming had two further serious heart attacks during the trial. Until

on August 12th 1964, nine months after the THUNDERBALL trial he suffered a

final fatal heart attack aged 56 and died in the Kent & Canterbury

Hospital. |

|

|

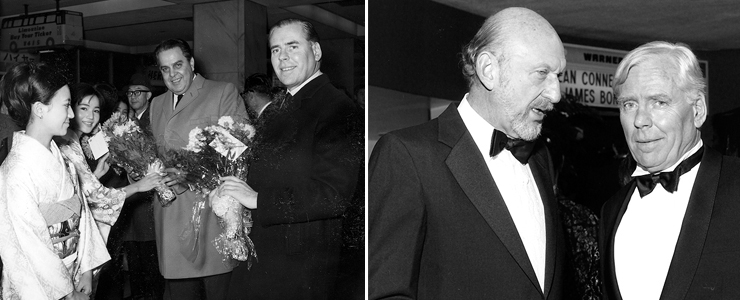

ABOVE: (left)

Thunderball executive producer Albert R. Broccoli arrives at

Tokyo airport with Kevin McClory ahead of the world premiere of

the 4th James Bond film which was held at the Hibiya Theatre on

December 9, 1965. (right) Never Say Never Again (1983)

director Irvin Kershner with Kevin McClory at the

UK Royal Charity Premiere

held at the Warner West End cinema, London on December 14, 1983. |

|

|

|

THUNDERBALL was eventually made into a film in 1965 by producers Albert R.

‘Cubby’ Broccoli & Harry Saltzman, who ‘presented’ the film for their

company EON Productions. Kevin McClory was credited as producer on the

film and, ‘Based on an original story by Kevin McClory, Jack Whittingham &

Ian Fleming’. The film grossed $141.2 million worldwide.

Jack Whittingham died of a heart attack aged 62 in Malta in 1973, his

contribution to the cinematic legacy of James Bond all but forgotten and

unrecognised.

In 1983 Kevin McClory acted as Executive Producer on

Never Say Never

Again, a remake of Thunderball. Sean Connery returned after 12

years to star as James Bond. The film grossed £137.5 million (estimated)

worldwide.

One of Kevin McClory’s closest ‘friends’ during the late 50s and 60s was

Jeremy Vaughn, who also knew Ian Fleming well, as his neighbour in

Jamaica. Quoted in Robert Sellers soon-to-be-published book

The Battle For

Bond, he recalls: “Kevin was a smooth operator, an attractive character,

but not a particularly pleasant one, certainly compared to his brother,

Desmond, who was one of the kindest people you could ever meet. If a

friend was in trouble, Desmond would always be there. Kevin would just

tell you to piss off, if you weren’t any good to him. He’s been very cruel

to a number of people over the years who thought they were his friends.

The overdriving thing with Kevin was that he just wanted to be a

celebrity, he wanted to be famous, he wanted to be, look at me, I’m Kevin

McClory. He probably had some semi-professional technical interest in

making a film, but he really wanted the glamour. He wanted to be amongst

the people that he thought he should be amongst.” “It was Kevin’s burning

ambition these [Bond] movies, but I don’t think he gave a damn who he

walked over and what he did in order to get there. Kevin had a project in

life and that project was Kevin McClory. Whether it was women, or money,

or making movies, or whatever, if that’s what I have to do for the Kevin

McClory project. Everything had a purpose.”

Kevin McClory was a rogue, but nevertheless a charming one, apparently. |

|

|

JAMES BOND NEWS |

Thunderball FACT FILE |

|