|

The Search For Bond Part 1 of an exclusive 3-part article |

|

|

||

|

The Search For Bond Part 1 of an exclusive 3-part article |

|

|

||

|

|

||||

|

One actor who might have been expecting a call from Broccoli & Saltzman around this time was George Baker. A few years before Baker was having lunch with Robert Clarke, head of Associated British Picture Corporation, where he was under contract, and who should walk in but Ian Fleming. “Ian came over to our table,” Baker recalled to me. “And said, ‘Now Robert, you’ve got to do these books and there’s your Bond sitting beside you.’ And Robert made the wonderful, classic remark, he said, ‘Ian, they’re good books, but they’ll never make films.’” Best known today for his role as Chief Inspector Reg Wexford in The Ruth Rendell Mysteries, Baker had been a minor leading man in the British cinema of the late 50s (coincidentally starring in a 1958 Roundheads and Cavaliers saga entitled The Moonraker), appeared on Broadway in a Noel Coward play and enjoyed an affair with Brigitte Bardot. All of which should have been enough to rank him pretty high on any list of potential Bonds. “When Broccoli & Saltzman came on the scene,” Baker continued. “Ian Fleming actually rang me up and said, ‘now George I’m going to put you up again because this time you’re going to get it.’ I was never even seen. I never got an interview. So that was that. Broccoli & Saltzman had different ideas, I guess.” Baker, however, must have left some sort of impression on the producers since a decade later they cast him as Sir Hilary Bray, head of the College of Arms, in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969), and then as a naval big-wig in The Spy Who Loved Me (1977). |

||||

|

|

||||

|

Besides Baker, who was Fleming’s other ideal Bond candidate at this time. Much has been written about his preference for David Niven. Whether Niven would have been any good is debatable, however fine an actor he undoubtedly was. One can’t judge it by his performance in the 1967 spoof Casino Royale, as that was played for laughs. Probably Niven was too refined, too gentlemanly to play a cold blooded assassin. Too old as well, he was already in his fifties by 1961. According to Sir John Morgan, Fleming’s step son-in-law, the author had another favourite, the little-known actor Edward Underdown. Born in London in 1908 Underdown was educated at Eton College before appearing in post-war British films playing stuffy types or military men. Fleming’s apparent enthusiasm for the actor was clearly not shared by Broccoli & Saltzman who never took Underdown seriously for the role. Although they must have made a mental note of the actor, later casting him as the Air Vice Marshal in 1965’s Thunderball (although strangely, his voice was dubbed by another English actor, Michael Collins, who had also re-voiced Gert Frobe in Goldfinger). |

||||

|

||||

|

Despite Saltzman announcing to the press that Bond was, “the acting plum of the year,” the search was getting so desperate that Daily Express columnist Pat Lewis helpfully announced a ‘find James Bond’ contest. ‘Competitors must be aged between 28 and 35,’ she wrote. ‘Measure 6 foot in height; weigh about 12 stone, have blue eyes, dark hair, rugged features – particularly a determined chin – and an English accent.’ Actors were told to send their photographs and vital statistics to the Bond producers and finalists would be chosen for screen testing at Shepperton studios with judges including Saltzman, Broccoli, Fleming and Patricia Lewis herself. According to Terence Young, some 50 screen tests were conducted on actors. |

||||

|

The winner of the poll was announced in late September 1961 as 28 year old London model Peter Anthony. ‘He’s often seen these days in tobacco adverts,’ noted Kinematograph Weekly. ‘Laying flat on his back, a straw hat pushed over his eyes, smoking a cigarette.’ Anthony was judged to be, in the eyes of the pollsters, ‘the man who came closest to 007.’ Broccoli even noted a, “Greg Peck quality about him… but unfortunately he lacks the technique to cope with such a demanding part as Bond at first try.” Anthony was ultimately rejected for lack of acting experience and had to console himself with the offer of a small role in Dr. No, which in the event never materialised either. |

||||

|

|

||||

|

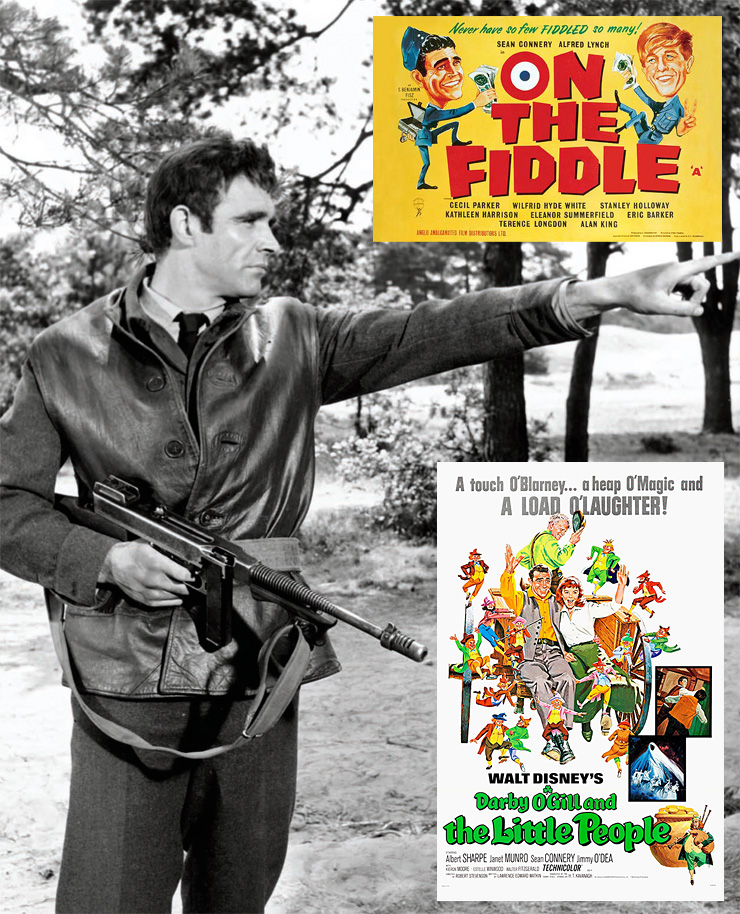

Another actor who scored highly in the poll was a certain Sean Connery, who Terence Young first met in 1957 when he directed him in a piece of melodramatic rubbish called Action Of The Tiger. “He was a rough diamond, but already he had a sort of crude animal force,” remembered the director. It wasn’t only Young who spotted the raw charisma pouring off the Scotsman but the female star of the film Martine Carol. ‘This boy should be playing the lead instead of Van Johnson,’ she told Young one day on location; hardly surprising since Van Johnson had the sex appeal of a haddock. Elsewhere other film makers who would play a significant part in the success of the early Bond films were being switched on to Connery. Editor Peter Hunt was currently working on a low budget comedy about two scroungers in the RAF called On The Fiddle (1961). Not much was expected of the movie produced by the Polish Benjamin Fisz, an associate of Saltzman; they later teamed up together to make Battle of Britain (1969). Even less was expected of the two leads, Alfred Lynch and Sean Connery. One evening Peter Hunt and Fisz were enjoying a meal at the Polish Club in London when they were joined at their table by Saltzman and his wife Jacqueline. It was during this meal that Hunt was offered the editing job on Dr. No and so the conversation naturally turned to how Saltzman was getting on with casting. ‘What about that Sean Connery,’ Fisz suddenly said. ‘Don’t you think he might make a good James Bond?’ |

||||

|

||||

|

This was a statement that took Hunt completely by surprise, since Fisz had originally been dead set against casting Connery in On The Fiddle when its director Cyril Frankel first suggested him. ‘He can’t act,’ Fisz had complained. ‘He’s just sitting around at the Pinewood canteen doing nothing and nobody will work with him.’ But Frankel wanted Connery. ‘I know I can get a performance out of him.’ And so reluctantly Fisz agreed and now here was the same producer putting him up for James Bond. ‘Well, Harry can see whatever he likes of the film,’ Hunt offered. Saltzman was keen on the idea, so Fisz and Hunt discussed which reels were the best ones featuring Connery and the next day shipped them over to the Bond office. “Now, what influence that ever had on the actual choice of Sean I don’t know,” Hunt later said. “But that’s my part in the thing.” When I interviewed Cyril Frankel for my book on the cult TV shows of Lew Grade’s ITC, he told me that Harry Saltzman turned up unannounced one day on the set of On The Fiddle at Shepperton Studios. “And he said to me, ‘Cyril, do you think Sean could play James Bond?’ And I said, ‘Standing on his head and reading a newspaper.’ And that’s how Sean got the part.” Almost at the same time in Hollywood Broccoli organised a screening at the Goldwyn Studios of a Walt Disney picture Connery had made in 1959, a charming Irish fantasy called Darby O’Gill and the Little People. It wasn’t the ideal vehicle to show off Connery’s potential as 007, playing as he did an innocent labourer, so an unsure Broccoli called up his wife Dana. ‘Could you come down and look at this Disney leprechaun film. I don’t know if this Sean Connery guy has any sex appeal.’ Dana caught a cab and arrived at the screening room. The lights dimmed and the movie began and it wasn’t long before Connery appeared. “I saw that face,” Dana was to recall. “And the way he moved and talked and I said, ‘Cubby, he’s fabulous.’ He was just perfect, he had such presence. I thought he was star material right there.” |

||||