| |

|

This interview with Bob

Dix (1935-2018) was originally available exclusively to subscribers of 007

MAGAZINE OnLine as part of

007 MAGAZINE Issue #50 in November 2006. The article was later

included in 007 MAGAZINE

FILES Live And Let Die File #1 in March 2011, and later available

as part of 007 MAGAZINE OMNIBUS #7

with different images. |

|

|

STEVE OXENRIDER in conversation with Live And Let Die’s CIA agent Hamilton.

Robert (Bob) Dix comes from a

proud tradition of acting talent. His father, Richard Dix, was a major

leading man at RKO Radio Pictures in Hollywood from 1929 through 1943.

During the silent era Richard Dix played cowboys, clean-cut American

heroes and Red Indians (Native Americans), most notably in the epic The

Vanishing American (1925). In 1931 he won a Best Actor Academy Award

nomination for his performance as the idealist Yancey Cravat in Cimarron.

His son, Bob, was born an identical twin to

Richard Jr. Bob Dix’s early career as an American character actor included

a wide range of musicals, romances, swashbucklers and many Westerns, among

them Young Jesse James. His friendship with Roger Moore started back in

the mid-50s when both he and Moore were under contract to MGM Studios in

Hollywood. Dix appeared with Moore in Interrupted Melody (1955),

The King’s Thief (1955) and Diane (1956). In 1956 he also

played Grey in the sci-fi classic Forbidden Planet. In 1969-1970

Bob teamed with cult horror/crime director Al Adamson to make five movies,

including Five Bloody Graves, in which he starred as well as served

as associate producer and screenplay writer. |

|

|

|

In the early 70s Bob Dix

was travelling extensively, writing, producing and making distribution

arrangements for independent film productions. 1972 found Bob in Slidell,

Louisiana, where he had gone to do research on alligator wranglers. To

gain insight into the lifestyle and secrets of these gator hunters, Bob

got a job tending bar in a honky-tonk called ‘The Happy Hour’. He was soon

dubbed ‘Bob the Bartender’ by the locals. “As a writer of screenplays, I

had learned tending bar was like being in a confessional - a great way to

get information. I was in the area when Roger and the production company

of Live And Let Die arrived in New Orleans (October 1972). I saw

his picture in the local paper and called him at his hotel.” |

|

|

The next day Roger

introduced Bob to director Guy Hamilton. “Guy discovered that the local

actor hired to play CIA agent Hamilton was afraid to do the sequence in

the streets of New Orleans. The crowd scared him. He froze up. Guy

Hamilton asked me to step in and play the part.”

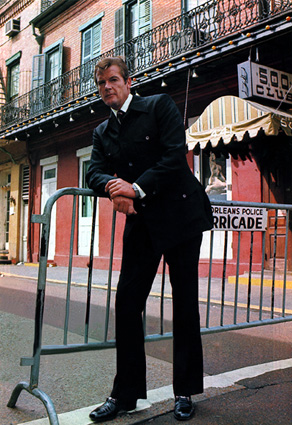

The pre-title sequence of

Live And Let Die features one of the most clever and bizarre deaths

in the entire 007 series. CIA agent Hamilton, in the French Quarter of New

Orleans on the trail of the evil Dr. Kananga, watches as a funeral

procession of pallbearers and mourners, accompanied by a brass band,

approaches.

“Whose, er… funeral is

it?” Hamilton casually inquires of a small black man [veteran jazzman

‘Kid’ Thomas Valentine (1896–1987) in a cameo role]. “Yours!” comes the

reply as the assassin stabs Hamilton in the stomach. Hamilton falls into

the street, the coffin is lowered over his body and in seconds it is

‘swallowed mechanically’ through the bottom of the coffin. The solemn

dirge of the brass band gives way to jazz as the mourners break into dance

and the coffin is carried off down Bourbon Street. |

|

|

|

|

|

To film the scene, a

coffin was purchased at a nearby funeral parlour, the bottom removed and

the interior properly rigged. Bob recalls, “It had rungs under it, front

and back. They dropped it over me in the street, I hooked my feet on the

back rung and pulled myself up on the front rung and hung there out of

sight. The ‘pall bearers’ carried me off down the street. I hung inside

until I heard ‘Cut’. It was like holding a ‘chin up’ when doing a pull up

exercise.”

The weather was not in

Dix’s favour during the four-day shoot. “We were half way through with the

killing of my character, Hamilton, and it started to rain. We had to stop

production after a day and a half into the sequence. As you know, you

cannot start shooting a sequence in ‘hard light’ and finish in the rain.

It won’t edit together. So we had to start over after the storm passed.” |

|

|

Roger Moore on

Bourbon Street, New Orleans |

|

|

|

|

Bob recounts working

alongside legendary greats Cameron Mitchell, Jack Nicholson and, on five

separate occasions, opposite John Carradine. “John was the Actor’s actor.

He could read a page of dialogue once and know his lines. He told me the

story of his early days in Hollywood. ‘People used to think I was part

vampire,’ John said, ‘because I only went out at night. The truth was I

owned only one set of clothes and it was a tuxedo!’”

Bob continues, “In

Cain’s Cutthroats (1971) John played a preacher who was also a bounty

hunter. The last day of principal photography we kept shooting from day

for day into night for night. We had been working almost 24 hours and were

on the last scene. To combat the cold of the night, John had been nipping

on some brandy. In fact, he seemed quite tipsy. But when he was called to

perform in the exterior scene on a western street with lots of dialogue,

he didn’t miss a beat. When the director called ‘Cut. Print!’ John just

about fell over. On the screen, as an audience, you would never have known

his condition.”

|

|

|

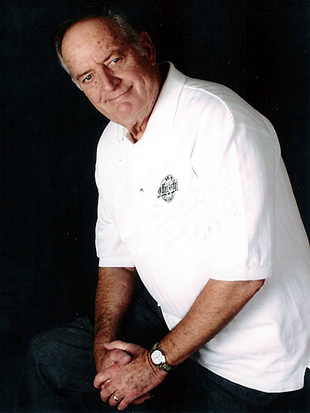

ABOVE: (left) October 26, 1972 Live And

Let Die director Guy Hamilton sets up a shot for the first of

two jazz funerals filmed on Bourbon Street, New Orleans. (ight)

American actor Bob Dix as CIA Agent Hamilton in Live And Let

Die (1973). |

|

|

|

Bob Dix left Hollywood

and acting in the mid-70s. Since then, he and his wife, Mary Ellen, have

become active in celebrity collectibles shows and as guest presenters at

film festivals across the U.S. Bob is also very involved in community

work, in particular sharing his understanding of the Bahá’í World Faith

throughout the Los Angeles area. In 1989 he was invited to the Native

American Film Festival in Gallup, New Mexico as guest speaker for the

first screening in over 60 years of his father’s silent movie Redskin,

one of the earliest sympathetic portrayals of the Native American. |

|

|

Roger Moore's

1973 diary of the filming of Live And Let Die. |

|

Roger Moore and Bob Dix

remain close friends today*. “Roger was and is a professional,

well-prepared actor. We had a good time working together and remembering

our youth. I’m really proud of the good work he is doing for UNICEF.”

In the book

Roger

Moore as James Bond, his 1973 published diary account of filming

Live And Let Die, Moore remembers reuniting with Bob in New Orleans.

“My mother would be absolutely gaga if she could see Bob Dix because he

looks exactly like his father who was her favourite screen heart-throb.

When I was a child she used to take me to see all his pictures.” Years

earlier Bob had presented Lily Moore with a framed 1-sheet poster of

Richard Dix’s 1939 western classic, Man of Conquest. “The poster

held a place of honour over her fireplace in England until the day she

died,” Bob recalls fondly. |

|

|

Richard Dix

(1893-1949) |

|

|

|

*Editor's note:

Since this article was written both Roger Moore and Bob Dix have passed

away. Roger Moore died at his home in

Switzerland on May 23, 2017. Bob Dix died on August 6, 2018 in Tucson,

Arizona, aged 83. It should also be noted that British based American

actor Shane Rimmer provided the

voice of Bob Dix in Live And Let Die when CIA agent Hamilton says the line “Whose, er… funeral

is it?” |

|