|

|

From the Archive

007 Issue #13 (1983) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

An edited version of

the following conversation with John Stears originally appeared in

007

issue #13, June 1983.

ANDREW PILKINGTON spoke with the two-time Oscar-winning special

effects technician John Stears on Christmas Eve 1982 at his home in the

village Jordans, near Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire. John had

originally seen the property from the air one day while undertaking a

‘recce’ out from Pinewood Studios. He fell in love with the house and its

grounds, and later purchased the property on which he and his wife Brenda

began an extensive renovation. John and Brenda also started and owned the

world renowned ‘Livny Borzoi Kennels’, producing many champion dogs

worldwide. John had an exceptional working relationship with Sean Connery

on the Bond films (and later in 1981 on Outland), no doubt assisted

by sharing the same birth date – August 25th. Nicknamed the ‘Dean of FX’,

John in later years eventually relocated with his wife and daughters Janet

and Jacqueline (both of whom work in the film industry) to Los Angeles,

until his untimely death aged 64 on his wife’s birthday, April 28th 1999. |

|

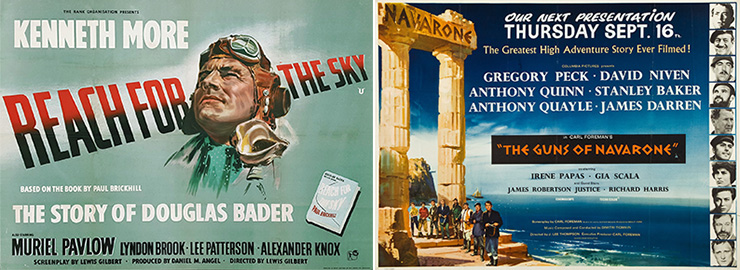

Has the job of a Special Effects man in

the film industry changed a lot since you first came into the industry?

It has changed an awful lot. If you go back to the 1950s you probably had

five SFX (special effects) men, optical people also being included in that

number. You’d work on a film and be involved in bits and piece because FX

(effects) then were not regarded with the importance they are today. It’s

really only because of… well, the Bond films, and The Guns of Navarone

(1961) and those kind of pictures that we got the reputation that we were

capable of doing rather unusual and rather good SFX. At this time in the

US cinema was running itself down and going into television production. So

they lost out with techniques and developments throughout that period, and

we got ourselves quite a good reputation for doing SFX. With the advent of

TV being a small format that does not lend itself to spectacular SFX,

people realised that if you had good SFX you would get people back into

the cinemas, and which has been proved with films like Star Wars

(1977) and Superman The Movie (1978). This is why SFX have now

become possibly the most important section of the movie industry.

Would your job in a film include a whole spectrum of effects?

What’s happened now is that from the original five or six guys, there are

now about 400. But now it as become so specialised that people are

concentrating on just one facet – because SFX is a very broad spectrum.

Having said that I still do the whole range of SFX but have no qualms

about bringing in experts to do various bits and pieces. I have an overall

knowledge of FX – so I can, and do, run the whole show. |

|

|

ABOVE: (left)

September 28, 1990 - 007 MAGAZINE Editor & Publisher Graham Rye

explains: “Unfortunately, John was busy the weekend of our

1990 convention at Pinewood

Studios, but popped in during our set-up day on ‘B’ Stage to

view all the props we’d uncovered and the vehicles we’d secured

for the groundbreaking event.” (top right) John Stears with his wife

Brenda and daughter Jacqueline chat with Andrew Pilkington at the

Thunderball 25th Anniversary

screening event held at The National Film Theatre on May 5,

1990. (bottom right) Main title designer Maurice Binder chats with

Dennis Hall at the National Film Theatre event as John Stears and

Production Designer Syd Cain (centre left) enjoy meeting up with

old colleagues. |

|

|

How did you originally become involved in the film industry?

I was living close to Denham Studios at that time. This was back in the

1940s, and I used to, when I was a kid, get under the fence surrounding

the studios and get into crowd scenes and things, and as a matter of fact

I became a child actor. I’ve always had my heart in the film business. All

my friends’ fathers were art directors or construction managers or

whatever, and it was always my aim to work in the film business. I went to

Harrow Art College (and also attended Southall Technical College) where

the curriculum involved silversmith work, fine art, photography, etc. –

but National Service was a thing that everybody had to do in those days.

So you couldn’t plan your future until that was out of the way. I was

actually working for the air ministry as a draughtsman, and could have got

deferred completely, but I opted out to go in the army and get it over and

done with – which I thoroughly enjoyed by the way. When I came out I

started making models for a firm in Richings Park.

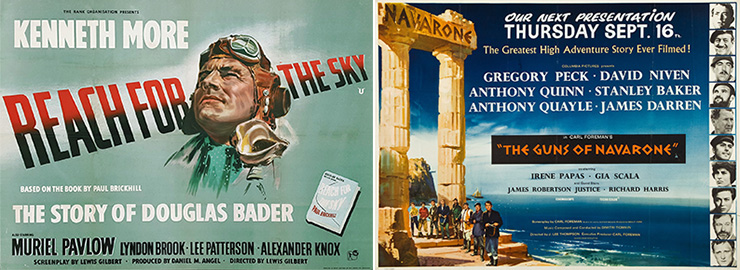

It was very difficult at that time to get

into the film industry because there was very little work about, but the

firm was given the brief for the film Reach For The Sky (1956)

starring Kenneth More as the WWII fighter ace Sir Douglas Bader, and

directed by Lewis Gilbert. I made the aircraft and took them down to

Pinewood and they asked me if I could operate them – I said ‘Yes!’, and

they asked me to stay on and work for them. I opted to work in the Matte

Department, and I also did some animation and spent five years with Rank

before the big collapse, after which I went freelance – and my career

started there really. |

|

|

|

One of the early films

on which you worked was The Guns of Navarone (1961). That film won

an Oscar for its SFX. Was that a difficult film to work on from the SFX

standpoint?

I didn’t do too many of the actual floor effects, but I became very

heavily involved with miniatures. I did the storm sequence.

You worked on the first James Bond film, Dr. No (1962), as an

assistant to Frank George – although you weren’t credited.

Yes, Frank went out to Jamaica, and I set up the miniatures back in

England. And then I became involved again with

‘Cubby’ Broccoli on a

dreadful film titled Call Me Bwana (1963) that had a lot of

effects, and then I was invited to do From Russia With Love (1963)

on my own, although Frank assisted me.

How did you become involved in the film Dr. No?

Frank George was in charge, being an old Pinewood man, and he knew my

capabilities and asked me to do the miniatures for him.

Even in 1962, the $1 million dollar budget for Dr. No was fairly

small for the times. Did you find that you were in a position where there

was too little money in the budget and had to go to great lengths to

achieve satisfactory SFX?

I don’t know why it is, I’ve always had this problem, and it’s never

changed. I’ve never had unlimited money to do SFX. I’ve always had to do

things the most efficient and cheapest way. I understand that there other

companies who have a large team of people working for them – I’ve never

had more than five or six staff.

Is that part of the appeal of SFX, the challenge of creating FX within the

available budget?

No, no no. I would like to have as much money as is necessary to do the

job properly – but even on Star Wars I didn’t get that! |

|

|

Can you relate an

example where you’ve used a simple solution to a SFX problem?

Yes, one picture does spring to mind. In fact I’ve never seen the finished

film – it was The Pied Piper (1972). They wanted scenes with

thousands of rats following the Pied Piper (Donovan Leitch), and had

spoken to various people about breeding rats. The picture really stood or

fell on whether we could do something using real rats. So I got some black

netting; and made some vacuum-formed plastic rats and hinged their heads;

put beads in for eyes and pulled the net with the ‘rats’ attached, so that

as the piper moved the rats appeared to follow – and it worked perfectly.

There’s an extensive use of projection work in the Bond films. What

influences your decision regarding the use of front or back projection, or

another projection technique?

Well, there is no process that is good for every shot, and you have to

work out which would be the best process for the shot in question. |

|

|

Some SFX technicians

actively dislike using projection techniques, especially the blue-screen

process because of the problem of matte lines. Is that a process you

dislike using and have you encountered problems when using it?

I am very reluctant to use blue screen ‘ad lib’. I had a very nasty

experience with Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968) because what happens

is that you don’t know what the results are until lots of things have been

put together, and you can’t go back and re-shoot it if things go wrong.

When you’re on a tight time schedule you’re totally in the hands of the

blue screen people and the labs that process the film. In other words, you

have to accept what they give you, and that’s a situation I hate to be

faced with, and since that very bad experience with the car going over the

cliff in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, I will never use it unless I have

technicians whom I trust implicitly to do the lighting etc.

What are the problems of shooting models in water, and can they be

overcome without enlarging the scale?

It depends. If you have a yacht in a mist on a very oily sea, then fine,

you can shoot with a small miniature. But if you have any life in the

water at all – explosions, or the like, then you are restricted because

there is no way of scaling down water. I think that was abundantly clear

in The Towering Inferno (1974). The thing that screwed that picture

up was the dreadful water coming out of the building at the end. It just

threw the whole thing away. That should never have happened. The model was

built too small. I always try to make my models as big as I possibly can. |

|

CONTINUED |

|