|

I

was going to ask you about the technology involved. I donít want to

get too technical, but I assume all these elements are fed into the

computer system, and somehow you are able to play about with it in

all kinds of different ways. Can you explain how this works in

nutshell?

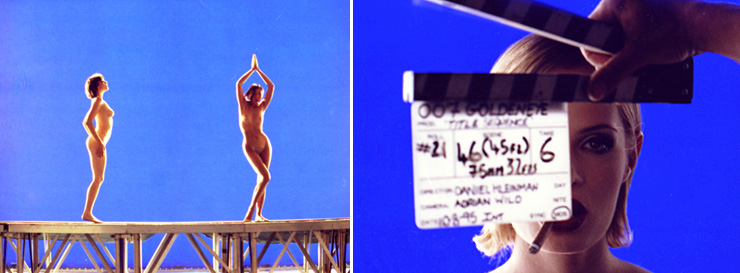

In simplified terms what happens is that we film

everything on a movie camera and it goes onto a piece of 35mm

negative. That negative gets scanned into a computer, but in the

computer it doesnít exist anywhere except as numbers on a disk, but

it comes on to a screen and you can do an enormous number of varied

optical effects on the computer screen. I shoot the elements against

blue screen because the computer takes away the blue and inserts a

different background. I can make someone smaller or bigger, I can

change the colour, I can distort things or change things around, I

can have 100 different elements that are on different pieces of film

all collaged together in one scene. Youíve got a paintbox device

which means if you have got wires or strings or poles you donít want

to see, you can retouch them out like you would in photographs, or

you can fly things around, or you can add smoke. You can do all

sorts of incredible things. The trouble is that itís very expensive,

it takes an enormous amount of time to do, and itís very slow. The

main reason itís slow is because the computer can only work at its

given speed. Itís unlike editing for TV or for adverts or anything

like that, which only ends up on tape to go out on TV where picture

quality is very low. For film, picture quality is very high. Film

has to be projected so it has to be very very detailed. So if youíre

saying to the computer, Ďwhat I want to do is make this girl look

like sheís got two heads and I want you to make them join together

so you donít see the seamí, it takes ages, and thereís lots of

complicated work to do. You do all the calculations, work it all out

and press go, and then it happens in the computer, but it does it

all incredibly slowly and you have to wait ages and ages while itís

processing. And thatís just one level. So if youíve got 20, 30, or

40 different levels of things going on, the actual processing of it

takes a really long time.

What you donít want to do is to be having ideas and

experimenting on this machine, so I took the film into a different

type of edit. A type of edit you use for TV, for adverts and special

effects for TV programmes, and I basically did the entire title

sequence on that system, which is a lot quicker but much lower

resolution. Then we went into this computer and said now do it

again, so in effect I had to do it twice. The good thing about it is

that it means that youíve got complete control and youíre not making

things up on this very expensive and slow machine, but the bad thing

about it is thereís no way of plugging one machine into the other

and saying, sort of, copy this. You have to remake it from the

beginning and just use it as a visual match.

It sounds very

frustrating!

It is very frustrating and very time-consuming, so we

were working literally around the clock. Even though itís only a 2.5

minute sequence it took several months to do with this new digital

technology, which has been used for doing opticals on films as

opposed to the old way, which was all done with projectors. It was

all kept on film it didnít go to computer. The advantage now is you

can see what youíre doing and you have much more control over it,

and you can do many more things, the downside of it is it takes a

really long time, and itís probably more expensive, but the end

result is more spectacular. Itís really amazing technology and itís

used for doing film opticals, but I think Iím probably right in

saying itís never been used before for doing one sequence which is

so long. I should think maybe the longest sequence itís been used

for in science fiction or fantasy films might be 10 to15 seconds,

and we were doing something which had to end up as being one

continuous piece of film for nearly 3 minutes, so in terms of

pushing the technology, it was really on the edge.

I

noticed in the Tina Turner GoldenEye video there was a Bond

silhouette featured. Did you have anything to do with that?

They took a couple of shots from the title sequence

and used it in the video but I didnít have anything to do with it.

How

long, including all the storyboard work and the preparatory work

before you actually get to physically shoot stock and then put it on

computer? How long did it take in total to produce the GoldenEye

titles?

From the beginning of having the ideas to actually

handing over the finished film, I think it might have been three

months.

Where did you

actually shoot the live action?

It was shot in a studio just outside London, just up

the A40, so actually because I wasnít using any sets or any real

locations it was all just shooting elements, where it was shot

wasnít particularly important.

Do

you know if you will be working on the main titles for BOND 18?

I hope they will ask me because Iíd like to have

another go. Luckily, everybody seemed to like them. I think a lot of

people who work on it and get involved in it....I think itís because

theyíre fulfilling their youthful fantasy, it definitely is for me.

If Iíd thought when I was 10 years old that I could be filming bits

for James Bond, I would be just so ecstatically happy. When I was

asked if I wanted to do it I just couldnít possibly turn it down. It

was just too good a thing.

Do

you consider yourself to be a Bond fan?

Oh yes, absolutely. Itís partly because itís part of

film history, which Iím interested in, I actually am interested in

Ian Fleming as a character and when I was a kid I collected the

bubblegum cards. Iíve still got a set of Thunderball

bubblegum cards, Iíve still got my Aston Martin that flies a man out

of the roof Ė itís all part of something that men of a certain age

did Ė all those things when they were a kid, and I did, and thatís

why I love it.

CONTINUE TO PART 2 |