|

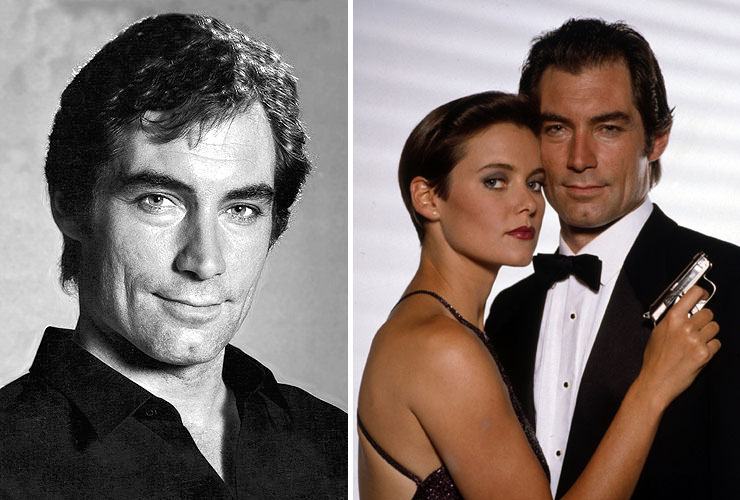

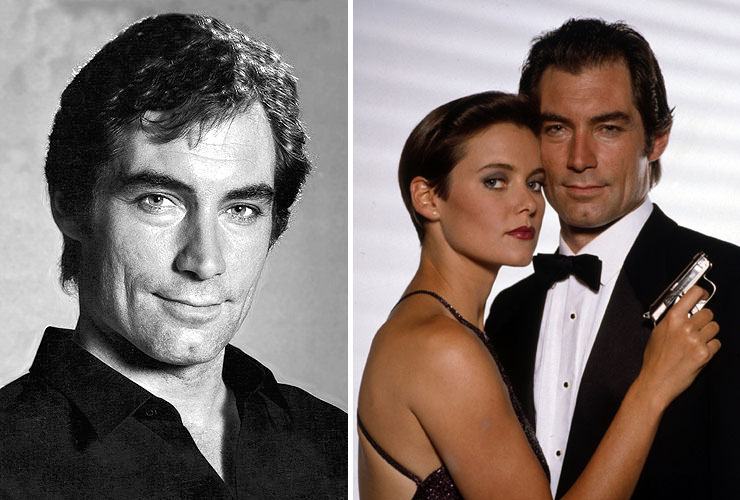

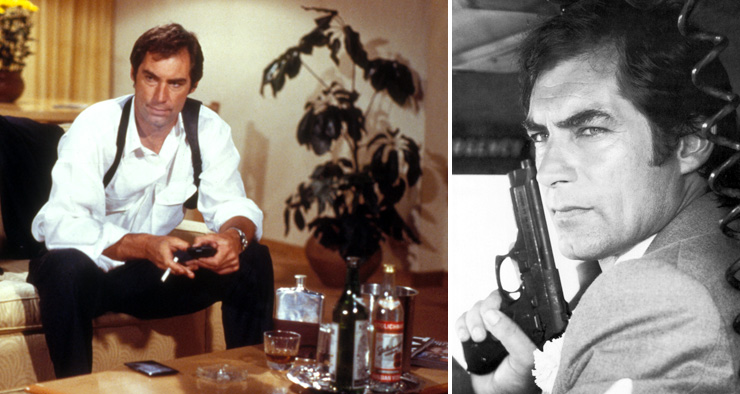

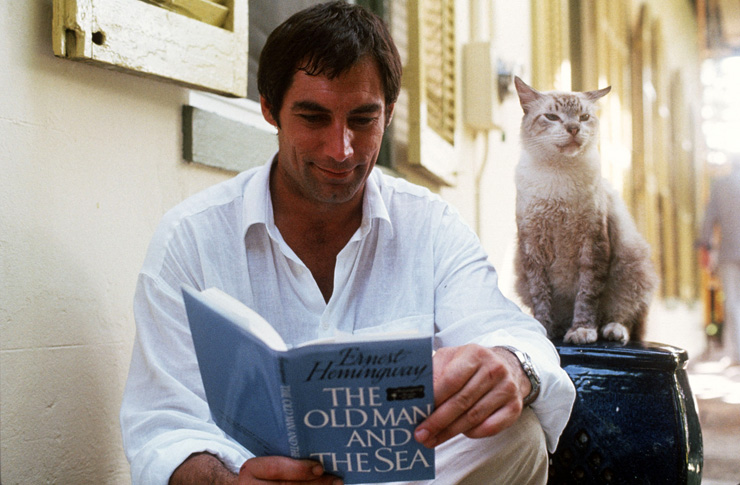

James Bond author RAYMOND BENSON was in

conversation with Timothy Dalton for 007 MAGAZINE

Issue #21 (Winter 1989),

and spoke with him about playwrights, the theatre, Ian Fleming Ė and that

man Bond. |

|

|

First of all, let me

say that I saw the new film, and I think itís great! I really liked it!

Well thank God for that, because if you donít, weíre in trouble.

I think itís the best Bond since, say Thunderball (1965). Itís

the kind of Bond film Iíve been wanting to see for years.

Good, good. Well, itís the kind of Bond film Ė weíve taken a big step, a

leap... itís back in the proper world, itís back in the right world of

James Bond. I think Ian Fleming himself would have liked this one.

Iíd like to start out talking a little about your theatre work. How do

you compare film making of this sort with the theatre? Does your

preparation for a role differ in any way?

No, I mean, itís interesting isnít it? Everyone seems to perceive that

thereís a huge difference between working in the theatre and working in

films, and there isnít really. The principle is the same. Youíve got a

story, youíve got a script, and your job is to understand it, to analyze

it, to comprehend its structure and then to see what part in that

structure, the part or role youíre playing, and then to understand your

character and try to fulfil the authorís intentions Ė bring it to life, I

mean itís the same principle. For example, if we were in a small theatre

with people over there, they would be able to hear us and relate to us

just as well. Obviously the theatre tends to be comprehensive, letís say,

in language, certainly in classical theatre, than movies, but the

principles just the same. |

|

|

|

Do you find it

difficult adjusting as far as the bigness of gestures in film and theatre?

In theatre you have to play slightly larger than life; did you find that

adjustment difficult?

Iím not entirely sure thatís true. I know it has the appearance of being

so and itís certainly true that some actors do play the large scale in the

theatre; but I think the best actors on stage are the actors that

certainly appear to be, as in film, actually truthful. The difference is,

of course, you can put a camera right in on somebodyís face, but both

mediums need an active energy of thought and feelings and itís amazing,

even in the theatre, how far absolute truth carries. And you must be the

same in a movie. Of course, there is that difference, you can do some

gestures - a look of an eye Ė that you canít do in the theatre, but then

you adjust your theatre performance to whether youíre playing the part in

a small theatre or a large one or whatever, but essentially youíre working

towards finding the moments that reveal the truth. It is the same.

Do you feel that doing Shakespeare is the ultimate challenge for an

actor?

No, I think the ultimate challenge is doing whatever youíre doing right.

Or as best you can do it. Shakespeare is undoubtedly one of the worldís

greatest, greatest writers. It has enormous challenges in its own right,

but thereís a challenge in anything, in any movie. Nothing can ever be

perfect, but itís perfection youíre aiming for.

Do you have a different approach to verse than you do to straight

dialogue? Do you follow the Barton-Hall method?

WellÖ verse has its own rules. But it depends on the kind of verse. You

can talk about two styles, you can be extremely effective in expanding the

language, expanding the verse, turning it into something else; I think

actually you should never remove anything from the necessity to

communicate its content. You should never take it off into Ďla di la di

laí. I mean the writerís written something Ė heís written a message.

Thereís content to what heís written. He wants to communicate something

through his writing. If heís put it in a strictly passive verse form,

thatís one thing; if heís put it in a loose, Iambic form, thatís another

thing. But never forget, certainly in a play, itís about one person

talking to another, wanting to communicate something to another, and for

me the best way to do it is to find the truth to that and to believe it

and communicate it like you mean it, so that the person youíre talking to

understands you and feels you, and so the audience does as well.

Shakespearean verse is wonderful, itís written in the sort of rhythms of

the English Language; Americans, if they can forget trying to play it

ĎEnglishí and just use their own accents, it brings Shakespeare to life

quite easily.

I think thatís the mistake a lot of American actors make.

Me too, me too! Because all that matters is that you communicate your

idea. Of course, in Shakespeare youíre talking about thought patterns that

are very large. Sentences and ideas can encompass three or four lines that

you must be able to hold in your head and then communicate it like you

mean it. I mean, everything has its demands. Pinter, who you would think

is writing very naturalistically, is not writing naturalistically at all!

He writes a sort of distilled essence of naturalism. Art is not reality,

but the appearance of whatever reality is appropriate.

Have you ever done Pinter?

You know, I never have. Heís my favourite playwright. Heís brilliant Ė

wonderful. I would like to. |

|

|

|

Do you have any

particular roles that youíve always dreamed of doing?

No, Iím sure some people do; but I think most actors probably donít,

because what your dream is, what you want to do, your desire, your goal,

your aim, is to play in wonderful pieces! I would hate to say wonderful

parts, because a part doesnít exist in isolation, it exists as part of the

play or movie script itself. I think if you just had one goal, it would be

awfully limiting Ė what would you do once youíd done it? The goal should

be in good work and hope to continue to be in good work, and continue to

be able to improve within that and take on all those challenges.

Do you have any favourite roles that you have done?

Uhmm, yeah I guess. Itís difficult to distinguish between those that were

successful and those that you liked. Itís also difficult to distinguish,

really, across a time span, because those you did ten, fifteen, twenty

years ago obviously are now much more a part of oneís own history. I can

only talk in recent terms rather than overall terms. Certainly I loved

doing the OíNeill play A Touch of the Poet. Iím very proud of that

production.

Are we going to get to see that over here in the States?

I doubt it. There was a moment when we could have brought it. But you

know, time, and other peopleís commitments. I wouldnít like to Ďre-doí it,

Iíd like to bring it here with the production we did. I think heís (Eugene

OíNeill) the greatest modern writer Ė others would argue with that, but

certainly one would agree heís one of the 20th centuryís greatest writers.

It was a forgotten play, and the way we did it, was I think right. And

several of the critics said that this must now be regarded as one of his

masterpieces. Well, if you can do that to a Ďforgotten playí then that of

course gives one tremendous satisfaction. So thereís that part. I loved

doing Petruchio in The Taming of the Shrew.

I would have thought

you could do Henry V really well.

Well! Itís funny you should say that, because The Taming of the Shrew

was a great hit, again through luck and judgement, and was a great

show. But of course its subject matter Ė I donít think thereís anything

wrong with its subject matter at all, fundamentally; itís saying that true

love exists when two people get to know each other. If they fall in love

with each other superficially on surface appearances, itís going to fall

apart. We see that story in The Taming of the Shrew. The two people

actually explore each other, get to know each other, struggle with each

other, and end up truly loving each other. But you know, a lot of people

see it as a chauvinistic or anti-feminist play. And I remember one of the

critics who happened to be hugely enjoying it, laughing all the way

through, decided to write for his paper a sort of feminist review. His

only comment about me was that I was the best Henry V of my

generation! (laughs) I donít know if youíve seen Hawks, but I hope

it will be out here soon. For some dumb reason, the Americans have decided

to cut out the parents from the movie, and that I think is important

because it gives the two guys their world of loneliness. Iím very proud of

it Ė itís a wonderful film. I would have thought it would have been

released here already. Well, youíre talking about two guys who have

cancer. Itís not actually about death, itís in fact about life, how

precious life is and how it should be seized and grasped and how. Why do

we always take tomorrow for granted? Why does it always take a crisis like

a war or some doctor telling you you have a dicky heart or a cancer to

make us value what it is weíve got. The premise of that, of course, is

death, so Iím sure people think itís not particularly a commercial

subject, although itís relevant to every single human being on the face of

this earth! We all know people who have been affected by cancer, and we

all have a life to live and we all waste a lot of it. |

|

|

|

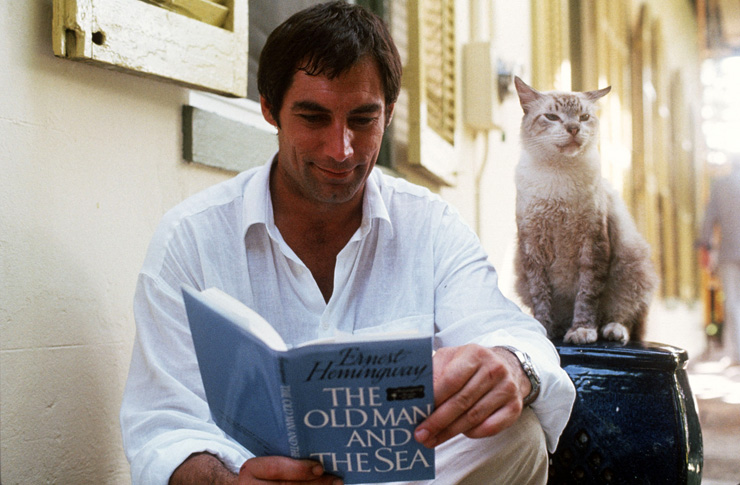

I think thatís a lot

of the key to Ian Fleming. Even though he knew he had a bad heart and that

he should cut down his smoking and drinking, and all that, but he embraced

life so much Ė he was always searching for sensuous pleasures and lived

life every day to the fullest.

Yes. That quality might not be reflected in the Bond movies, but itís

certainly reflected in the Bond books.

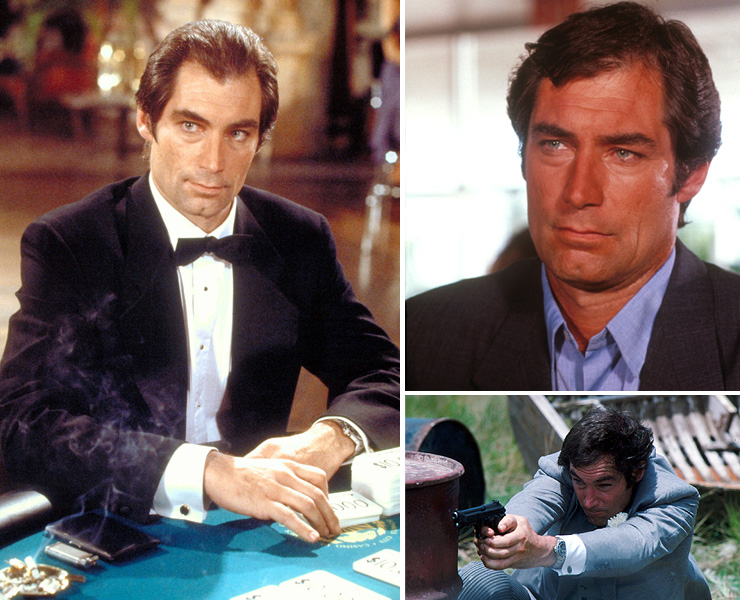

How did you prepare yourself for Mr Bond?

You know the answer to that question, donít you? Itís simple. He wrote it.

His books gave rise to the first movies. Those movies have gone on for 27

years. He must have done something right. But anyway, beyond that, as an

actor the only way I could approach anything is, I mean I feel my duty as

an actor is to work with the author, to reveal the authorís intentions.

Particularly CASINO ROYALE, which I think is splendid.

Itís an amazing first novel.

Yeah! That doesnít mean you can bring all those qualities to all the

movies because each movie is different and each story is different, and

anyway theyíre not all written by Ian Fleming. But certainly, theyíre

written of that world, weíre talking about a Bond movie, so itís Fleming.

Within the criteria of the framework of what is possible. I mean, I loved,

for example, I found it quite surprising, one of the reasons why I liked

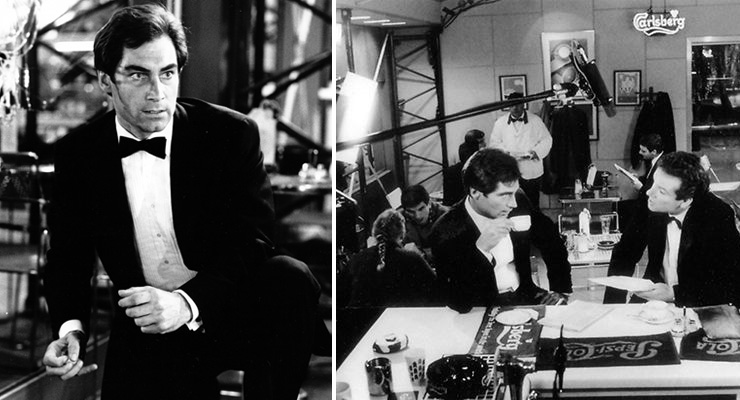

The Living Daylights as a basic script, that terrific moment with

Saunders when he says, well fuck it, I donít care if he does fire me. And

Fleming was always writing about this thing called, and we use the word

Ďacidityí in the movie, but it was cut. |

|

|

You know that was at

the very beginning of the movie, and as soon as I saw that scene, I

thought Ė wow, this is Bond!

Well, itís a thing Fleming always, always talks about because the man is a

paradox. He is a killer! A murderer! Heís a bad lad! But heís on the side

of good! And how do live with this paradox? And thatís interesting! So I

was very pleased to see that in The Living Daylights.

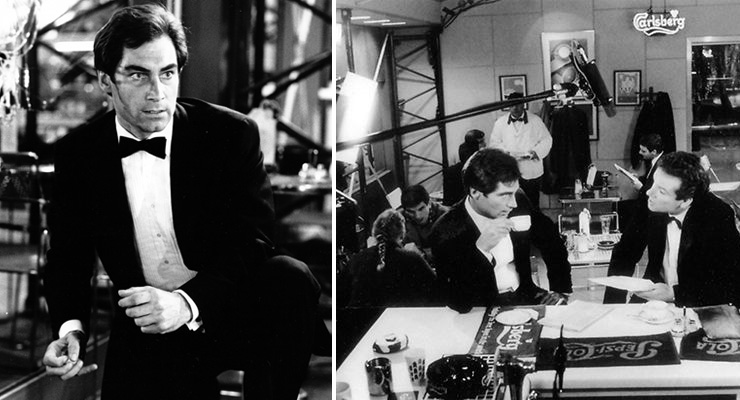

Thereís even more of that in Licence To Kill.

Do you think so?

Yes!

Good!

I mean the scene with you and M. You punch your way out of your meeting

with him!

Yes. Thatís never been done before! No. And it certainly reflects his own

determination to do what he believes is the right thing. |

|

|

What aspects of the

character did you find appealing or unappealing when you first started

working on it?

I donít think like that. And as an actor, you start with the story, and

Iíd never done an action-adventure thriller before. And I knew the danger

of taking on something like Bond was immense; you know that if it hadnít

worked, it would have been a very serious, serious problem for me

personally. And I think, in many ways, that perverse thing in all of us

wants to take on a challenge and risk oneself, and I wanted to see if I

could overcome that challenge and get these movies back into being in a

world that I consider to be James Bond word. I mean if you like the books,

if you like the early films, why do you like them? Sure, theyíre

fantasies, sure theyíre wonderfully exciting thrillers, but whatís the

purpose of the things? Well, we know about heroes, whether theyíre Raymond

Chandler heroes or western heroes or James Bond heroes; but essentially,

you want to go and sit in a cinema in safety and lose yourself in a world

of imagination, into a dangerous, exciting world that hopefully one will

never actually be part of. But thatís what a Bond movie should be. Itís

not a cartoon. Itís not a light hearted tongue-in-cheek comedy, however

entertaining, but thatís not real Ė I wanted to see if Bond could get back

into that. But talking about what do you like about it, you just think:

does the story work? Can I make the part work within the story? Whatever

the guys qualities, you can play the sleaziest, nastiest man whose got

qualities youíve got no admiration for at all, but as an actor itís still

part of your job and itís one of the interesting challenges of your job Ė

can you play this part? Whether you like the qualities or not doesnít

really enter into it.

What kind of physical preparations did you have to make?

None.

Did you have scuba training?

Well, that is one thing Ė I did have to learn to scuba dive.

CONTINUED

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Due to recent U.S. import

tariffs and significant increases in UK Royal Mail charges,

we are unable to supply 007 MAGAZINE to customers in the

United States at this time. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|