|

|

|

|

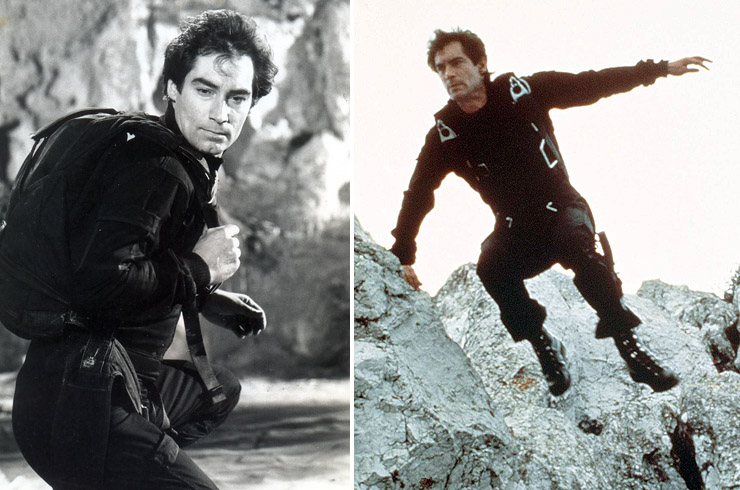

Parachuting? Did you

do any of the parachute stuff?

(smiles) Well, we donít talk about that. I think itís safe to say now I

wonít tell anybody about how the stunts are done, how effects are made,

because thatís all part of the enjoyment. You remember, as I do, when we

were all a lot younger and watching Dr. No for the first time and

how you were on the edge of your seat when the tarantula crawls up his

chest Ė if you knew there was a piece of glass between him and the

tarantula, the moments blown!

But you did some

actual scuba work?

Yes, I did learn to scuba dive. Itís important. I am involved in all the

action. I am involved in every single, whatever you want to call it,

action sequence or stunt sequence, I am involved in it all. Because itís

an action-thriller. Youíve got to know that Bond is there! Youíve got to

be with Bond in his moments of danger. Otherwise youíre conning the

audience. And youíve got to be able to get a camera in there. So I get

involved in everything. That isnít to say that there arenít stuntmen. But

nobody does anything dangerous Ė the skill is to make it appear dangerous.

But I did get out of the helicopter on the wire.

Unlike some of the other actors who have played Bond, like a true

theatre craftsman, I can really sense that youíre searching for and using

the subtext. For example, your reading of the line Ďshaken not stirredí

was so freshÖ

Oh thatís right, he uses it as a put down to her.

I mean, we know youíre

ordering a drink, but the subtext is Ďget out of here, I want to be alone

with this womaní. Does the director, John Glen, work with the actors at

all in Ďbringing out the subtextí, or is that your own work?

Itís a collaborative effort. I mean, in the movies the director must be

the most harassed, under pressure man on the entire set. He doesnít want

to be telling people how to do their jobs, heís got to be responsible for

the movie and for getting it organised and shooting it and making his

movie. He doesnít want to be telling the lighting cameraman how to light

it, you know, he wants people to come to him with ideas to choose from,

with alternatives, with input. |

|

|

|

Do you get any

rehearsal time?

We get a bit, but you donít rehearse films much.

Do you wish you had more rehearsal time?

Well, sometimes and sometimes not. It depends on the nature of the scene.

But what we will generally do, as on any film, is something that Iíve

always insisted on Ė I mean, I havenít had to insist on it, itís just the

way one should work Ė you take the scene and you work the scene Ė maybe

briefly, maybe quickly, but youíll explore the scene and then you do it

bit by bit. You have to know where youíre going, you have to know whatís

what. But real rehearsal, no thereís not a lot, and sometimes, it depends

on the actor, the spontaneity, as long as you know what the scene is

about, as long as you know what youíve got to achieve in the scene, as

long as you understand its physicality, itís sometimes good not to

rehearse because providing the aim is in your head, the spontaneity is

important in itself. In theatre what you always notice is that sometimes

first rehearsals are marvellous, but then you always get stale after a

while; but then after a further while as a result of the exploration

youíve done, as a result of the conclusions youíve come to, it starts to

come fresh again. But you do go through that stale patch. That mustnít

happen on film Ė youíve got to capture moments of truth, aliveness, and

spontaneity.

Do you think Bond could work on stage? If the opportunity arose, would

you be interested in playing James Bond in a stage play, if it was done

the right way?

I couldnít really see it being done on stage. I mean its very essence is

not introspective.

Something low key like CASINO ROYALE?

Well, CASINO ROYALE, other people have the rights of course, but to make a

film like CASINO ROYALE properly, it would be so outside what is currently

accepted as James Bond on film, but it would make a bloody good film. Done

as written, it would make a great film. |

|

|

|

I see it black and

white, 1953Ö

Done as a period piece, yes, Iíd love to do that film, but other people

have the rights, and it would be so far outside what people would expect

of James Bond, who knows how it would be received Ė but itís a cracking

good story. But on the theatre, I couldnít imagine a James Bond story in

the theatre.

How has playing James Bond changed your life, positively and

negatively?

Hardly at all negatively Ė Iím very happy to say that. Positively Ė

professionally, of course, because the nature of our world is a commercial

world and if you can have a commercial success then youíll get a lot more

offers.

What about the legions of fans whoíll hound you for autographs for the

rest of your life?

Well, thatís all bollocks, isnít it? Itís all bullshit. That is not true.

You get all that when youíre in a publicity situation. There might be a

few people outside the hotel, but those are the professional autograph

bounty hunters, or the paparazzi. But you or I could walk down the street

here or in London, and people would certainly recognise me, but nobody is

going to bother me. Most people on the street are healthy, decent people

with their own sense of self-respect and integrity and theyíll treat you

regularly if you behave regularly. If on the other hand you behave like an

asshole, and go around with battalions of bodyguards and limousines and

press and photographers and all that, and make an issue out of it, then

itís a different story. The majority of people who go and see a movie or

play, if they like it, they come out and say that was a bloody good film

or play, and so on, but theyíre not going to go around to the stage door;

theyíre not going to write and ask for an autograph. Only a tiny

percentage of them will. And the bulk of that percentage are people who

really just want to say that was great and would you mind if I had an

autograph. The kind of thing youíre talking about is the tiniest minority,

and itís a bit odd anyway. |

|

|

|

The Bond world has

that group, you know, like Star Trek and Batman Ė itís got

its legion of fans. Itís going to last.

Frankly, I love it from some. Someone in the airport the other day just

said, ĎI saw the film Ė terrific Ė thanksí, and walked on. That felt

great. Thatís how I would react, thatís how you would react, if you see a

performance you love, and if you ever met the guy, maybe Ė but even if you

did, even if you were in a restaurant you might not want to disturb him

having his dinner, youíd just think ĎOh, thereís...í. But some people make

a profession of being a fan. Itís on the edge of abnormality in a lot of

ways. Itís gone beyond genuine care and respect. And thereís not many of

them. The press tend to build up all the screaming hoards. Sure, if you go

to a premiere itís par for the course, itís everybodyís game. New rules

are set. But just going down the street to the pub, the real world is not

a problem.

So you donít get much of that?

And Iím very pleased. As an actor you canít cut yourself off from your

roots; you canít cut yourself off from the foundations of your work, and

they are people - itís people who you act, itís people you take parts in

stories, life is about people. If youíre stuck up on some hill surrounded

by barbed wire and guards Ė how could you be in our business if you remove

yourself from our world?

What was your first

initiation into Bond Ė the books or the early films?

It was the film Dr. No. |

|

|

Can you remember what

really struck you about that?

Well, I donít remember how old I was, 15 or 16 Ė 1962, I must have been 15

when it came out. And it was splendid, if you think about how things were

at that time; I donít know about America, but what kind of movies were you

watching? War stories, drawing room comedies out of the fifties, and this

film Dr. No just came and took the cinema by the scruff of the neck and

banged it right down into today. As well as giving us a whole new area of

adventure story to explore. And it was terrific. And then they went on.

The miracle is that theyíre still as popular as they ever were. That is in

great part due to the essence of the stories, because they are hero

stories, and hero stories have crossed all cultures, all history; people

need heroes. But theyíve always been done bloody well. Mr Broccoliís never

attempted to cheaply exploit a previous success. Heís always tried to make

sure that every single film is done better than the one before or

absolutely as best as it can be. The money spent, the talent...

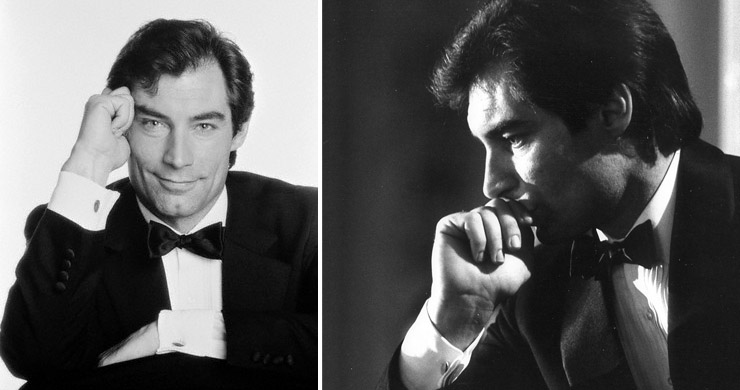

Objectively how do you think you compare to other Bonds?

I donít think about it. Itís a futile exercise. It becomes so complex.

Itís true that Iím acting in a public sense, and I would include myself in

that, that over 27 years of Bond movies, everyone has their own idea of

what a Bond movie is. The fact that every single movie is tremendously

different from the other. I mean how can you look at a film like From

Russia With Love, a Bond film and compare it with Moonraker?

Itís such a different story and itís such a different style. Connery was

in a certain kind of movie and even the style of those movies began to

alter. The first movies, if you look at them now, they have a different

effect than they had when we watched them originally. Theyíre of their

time, but they were in general wonderful adventure thrillers. The Moore

movies were light-hearted and tongue in cheek technological extravaganzas.

You canít compare Moore and Connery because they were in such different

films. I leave it for other people to make comparisons. The other

interesting thing is, of course, and the problem we all face, is that if

nobody had ever heard of a James Bond movie, if there had been no James

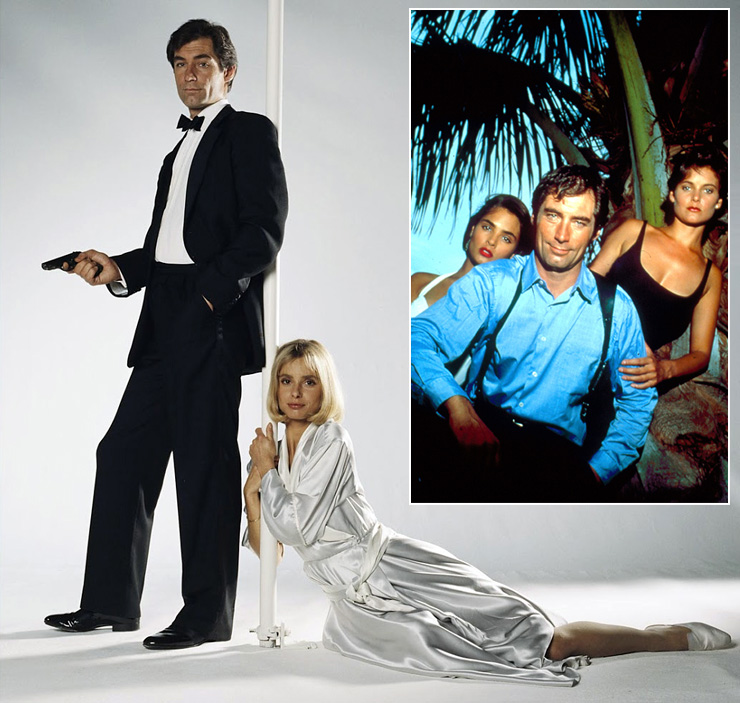

Bond movies ever, and The Living Daylights or Licence To Kill

or any of the movies was just released as a movie in its own right, the

public opinion and appreciation and reaction would be completely

different! Itís because one is carrying all this history. Itís like going

out and playing Hamlet. How can anybody do Hamlet these days? Everyone

knows the bloody story, nobodyís surprised. Nobodyís been taken by

spontaneous reaction. |

|

|

Given that Bond is

something of a role model for young people...

A role model?

Sure, when I was a kid and saw Goldfinger, I was buying all the

toys and running around with my eyebrows raised and all that...

Connery didnít raise his eyebrow! (laughs)

Do you think Bond should de-emphasise any of his traits? Do you think

you have a responsibility as an actor to...

I donít think that Bond is a role model or that he should be a role model.

Heís only part of a particular kind of story. I donít think anyone should

grow up wanting to go around killing people. I donít think anyone should

grow up wanting to be a secret agent...

I did! (laughs)

Well, weíre in a different world now arenít we? In those days we all had a

sense of intrigue and mystery and a sense of justice and rightness about

our countries. In this day and age, I donít think people have too much

regard for the work of their own secret services, do they? I think itís

certainly well worth believing in some kind of truth and justice. But Bond

is not a paragon of virtue; heís a man riddled with vices and weaknesses

as well as strength. But that is the nature of the man, and the nature of

the world he lives in, but I donít think he should be a role model.

Do you think he should practice safe sex on screen?

I donít think weíve ever seen sex in a Bond movie. |

|

|

|

Licence To Kill

is probably the most violent Bond film ever made. Do you have any comment

on that. What would you say to critics who might attack the film for being

too violent?

I wouldnít say anything to the critics Ė they have every right to their

opinion. I donít know that it is the most violent Bond film, because you

must judge it in terms of its time. Donít forget that Dr. No

created an outrage, not only for its violence, but for its sex. But

thereís no sex in Dr. No at all, so what were they talking about.

What they were actually talking about in í62, although we think of the

sixties Ė the sixties didnít really begin until the mid-sixties, í62 was

still the fifties Ė what they were talking about was Ursula Andress coming

out of the waves in a bikini! It was the first time weíd seen a bikini!

That was an outrage sexually! As for the violence Ė it was given an ĎAí

certificate (in Britain this classification meant you had to be

accompanied by an adult to see the film) because Bond gunned down an

unarmed, defenceless man, you know - ĎYouíve had your sixí, now that for

its day was considered a) wrong, morally wrong and b) very violent. Now

everything in our movie, first of all Iím pleased that our movie is more

violent, because that is the world that James Bond must live in, and if

you donít like that, Iím sorry, donít go and see the film. Weíre not

making movies for kids; weíre making movies for adults Ė itís an adult

fantasy that kids will enjoy. Yes I agree that kids can see this, and they

should go and see it, but weíre not making the film for 11 year olds!

Weíre making the film for the child in all of us adults. It is a violent

world he inhabits Ė itís the very nature of a Bond movie. But whether itís

more or less violent is relatively speaking; I mean everything is classic,

isnít it? I mean, people getting fed to the sharks, to the piranha fish,

people getting set on fire, people being shot with harpoon guns, people

being shot with bullets, Bond killing people Ė theyíre all classic

elements of the genre! In a modern world you do them to the height of your

skills, and is it violent? Yes, it is violent, but you donít see the

violence. What the film makers do, which is brilliant is they create the

tension, the extreme tension of violence. The violence is all in the mind.

If Ian Fleming was still alive today and you had some influence on how

he was going to take the character in a certain direction, would you have

anything you would say to him? Where would you like to see Bond go or

happen to him?

Well, if Ian Fleming was alive today, Iíd love to spend time talking with

him about the character, and Iíd love him to be involved in making the

film, as Iím sure everyone in our organisation would be. But I think Iíd

leave the creative ideas to him.

Where do you think 007ís future lies as far as the nineties are

concerned?

I donít know. Itís always important to remember that he doesnít really

operate as a spy or a member of the secret service. At the end of CASINO

ROYALE, Fleming did make him a hero, the man who does it virtually alone.

And that theme is universal Ė the hero theme, no matter what sort of hero

youíve got, a white knight, or a man of many paradoxes, youíve just got to

make sure the stories have some modern relevance, and they mean something

to a modern audience, and then rely on creativity and imagination to

create those stories. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

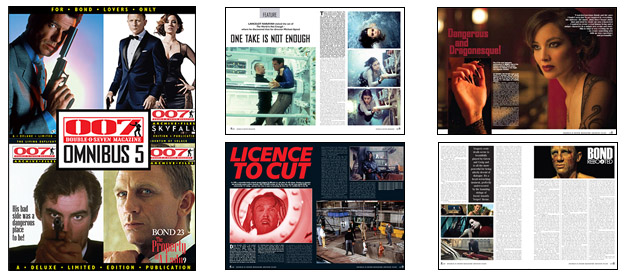

Due to recent U.S. import

tariffs and significant increases in UK Royal Mail charges,

we are unable to supply 007 MAGAZINE to customers in the

United States at this time. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|