Moonraker

|

||

|

||

Moonraker

|

||

|

||

|

|

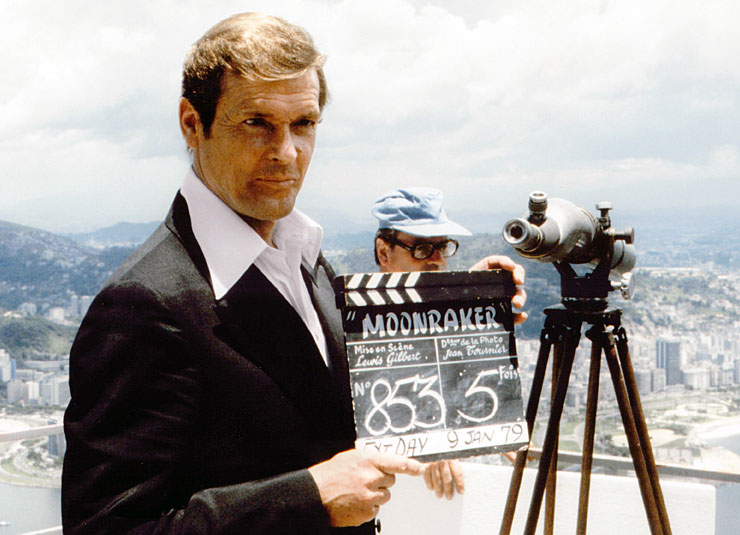

By the time Roger Moore was well enough to fly the production was three weeks behind schedule, and producer ‘Cubby’ Broccoli worried if his $32-million gamble would ever pay off. Flying from Paris on Concorde Roger Moore arrived in Rio de Janeiro on January 7, 1979. Still in pain, Moore got off the plane, got dressed and made up, got back on Concorde and disembarked as James Bond, and that is the sequence used in the finished film! Two days later the kidney stone was passed and filming resumed with the sequences on Sugarloaf Mountain and the Rio carnival. |

|

|

As ever the stunt work on Moonraker was outstanding, and the cable-car fight between Bond and Jaws was no exception, with the stuntmen putting themselves in real danger for the sake of the film. Richard ‘Dickie’ Graydon doubling for Roger Moore, at one point fell over the side of the car without first having his safety harness attached, and simply clung on for dear life thousands of feet above Rio de Janeiro. Martin Grace doubled for Richard Kiel and the resulting fight (although marred by the inclusion of poor rear projection) showcased that Bond films still did things for real, an ethos that carried on well into the digital era. Martin Grace himself was seriously injured when doubling for Roger Moore in 1983 during the train sequence in Octopussy, when he hit a concrete post at the side of the track whilst hanging onto the side of a carriage. |

|

|

|

Whilst in Brazil the second unit also filmed at Iguazu Falls for the sequence where Jaws’ boat goes over the edge of the raging torrent. The boat chase itself had been filmed in Florida but a shot of the falls was needed for the end of the scene. This proved easier said than done as the full-size boat became stuck on rocks at the top of the waterfall, and special effects supervisor John Richardson elected to be suspended beneath a helicopter in an attempt to dislodge the craft, in a stunt as dangerous as any other performed in the film. Ultimately all attempts to free the boat failed and the shot was later completed at Pinewood Studios by visual effect supervisor and miniature specialist Derek Meddings. |

|

|

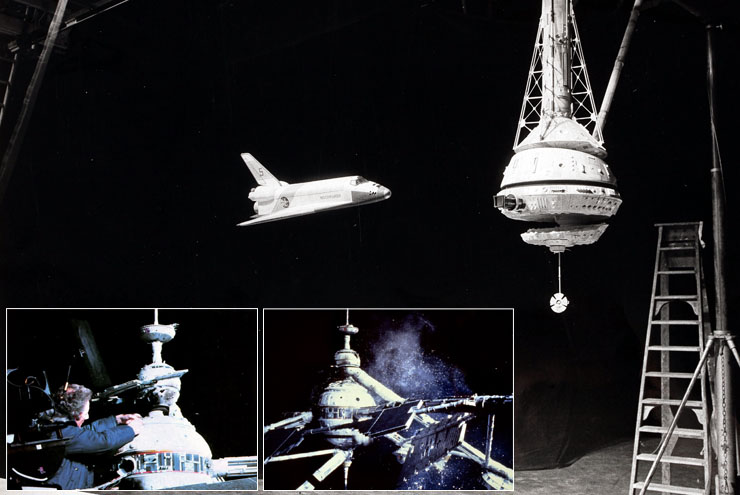

Despite every attempt to derail Moonraker with juvenile humour, the one element of the film that has stood the test of time are the visual effects by Derek Meddings. Originally engaged for Live And Let Die (1973), Meddings also created the miniatures for The Man With The Golden Gun (1974), and The Spy Who Loved Me (1977), with his realistic models of Atlantis and the Liparus super tanker being particularly memorable. For Moonraker Derek Meddings opted for the risky method of multiple exposures on one piece of camera negative; rather than filming separate elements and combining them with an optical printer, which is how the outer space effects in You Only Live Twice and Diamonds Are Forever had been achieved. The miniatures in Moonraker were filmed against a black background and the film then wound back in the camera and another element exposed. Any mistakes would result in the loss of days, if not weeks of work. This technique was as old as cinema itself, and most famously used by Stanley Kubrick for the spacecraft miniatures in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). |

|

|

Although time-consuming and fraught with danger, the technique gave a better end result and it is a testament to the patience of Meddings and his crew that this method was employed. Derek Meddings and his team of Paul Wilson and John Evans were nominated for an Academy Award for their work on Moonraker, but ultimately lost out to Alien. The idea of also showing models and effects on monitors, or projected into the walls of Drax's Amazon headquarters, adds verisimilitude to many of the shots making then hard to identify as miniatures. Before the actual launch of the US space shuttle, Moonraker showed us believable space sequences, aided by the superb realisation of Ken Adam's space station design. For the climactic destruction of the large space station miniature, Meddings came up with the innovative idea of destroying the structure with shotgun blows filmed at high speed. Work on the visual effects was completed on May 14, 1979 and the film went into post-production in readiness for its release just six weeks later. |

|

|

|

Moonraker proved to be a turning point in the James Bond series, not only because it took the films to new levels of technical excellence and narrative absurdity, but is also proved to be the last 007 film for two key figures who had been involved since 1962. Bernard Lee (1908-1981) [pictured above at the Moonraker premiere with his second wife Ursula] was arguably the most accomplished and well-known actor to appear in Dr. No and received an ‘also starring’ credit on the film's posters. In a career that dated back to 1934, Lee often appeared as policemen or dependable officials in such classic British films as The Fallen Idol (1948), The Third Man (1949) and The Blue Lamp (1950). His casting as M in 1962 brought a sense of reality to the James Bond films, although in later years his role was somewhat diminished to that of comedy straight-man. Bernard Lee died on January 16, 1981 aged 73. Moonraker was also the last James Bond film to be designed by Ken Adam (1921-2016), who had worked on six earlier outings beginning with Dr. No in 1962. His outlandish style set the series apart from anything else, and his larger-then-life sets were an important part of the Bond formula throughout the Sixties and Seventies, and no amount of CGI can replace the fact that for the most part Adam's creations were all realised at full-scale, and every penny spent on them showed on screen. Moonraker also marked the final James Bond film directed by Lewis Gilbert. The next five films in the series would be directed by Moonraker's editor John Glen. |

|

|

|

Moonraker premiered in London on Tuesday June 26, 1979 and became a record-breaking phenomenon across the UK in the months that followed. The film was re-released three more times in the UK on double-bills with The Man With The Golden Gun in 1980, The Spy Who Loved Me in 1981, and finally with For Your Eyes Only in 1982. Whatever James Bond fandom may have thought (or still think) about Moonraker, its huge international success proved once again that ‘Cubby’ Broccoli and EON Productions were still major players in the motion picture marketplace. Its excesses did not go un-noticed by the filmmakers or critics, and the next entry in the series was the previously postponed For Your Eyes Only, which returned James Bond to earth and drew upon Ian Fleming's short stories for its inspiration. For many fans that film was a welcome return to reality, and whilst not as costly or successful at the box-office, it took 007 into a new decade where it became increasingly more difficult to compete with American blockbusters. Moonraker may not be up there with the likes of Goldfinger or On Her Majesty's Secret Service as an icon of the series, but for many fans this was their first introduction to James Bond, and the film will always hold a special place for them. |

|

From the eye-popping opening freefall sequence, Ken Adam's spectacular sets, classy cinematography and iconic locations, to the groundbreaking visual effects and John Barry atmospheric score (his use of Elmer Bernstein's theme for The Magnificent Seven notwithstanding!), Moonraker has many elements to admire. Whilst the proclivity for schoolboy humour and over-the-top stunts didn't go away completely, it was a long time before another film in the series reached comparable heights of commercial success. Happy 40th anniversary to the James Bond film that was literally out of this world! |

|

|

|

|