Moonraker

|

||

|

||

Moonraker

|

||

|

||

|

||||

|

Outer Space Now

Belongs To 007. |

||||

|

The end credits of The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) had announced that the next film in the series would be For Your Eyes Only, but in the wake of the huge commercial success of Star Wars (1977) it was decided to film Moonraker instead, since Ian Fleming's original novel would lend itself more readily to a space themed story. Every major studio was racing to release their own science fiction based films in order to cash-in on the phenomenal worldwide success of George Lucas's Star Wars, and Steven Spielberg's Close Encounters Of The Third Kind (1977). 1979 saw the release of many films with stories set in space including Ridley Scott's Alien from 20th Century Fox, Buck Rogers In The 25th Century from Universal, Star Trek: The Motion Picture from Paramount, and at the end of the year even Walt Disney Studios jumped on the bandwagon with The Black Hole, which featured a memorable score by John Barry. Moonraker was released in the UK on June 26, 1979, and three days later in the United States. The eleventh James Bond film topped the box-office in the UK that year, but only managed 9th place in the USA, being out-grossed by Alien and Star Trek: The Motion Picture. However, Moonraker went on to gross over $210-million at the worldwide box-office becoming the most successful James Bond film until GoldenEye in 1995. Since its release Moonraker has divided fans, with many considering it to be the absolute low point of the series thus far. Although it does represent the worst excesses of the franchise, and its commercial success hard to reconcile, Moonraker proved that like You Only Live Twice before and Die Another Day that followed, it was to be a turning point in the series, prompting the filmmakers to return to a more believable storyline with their next instalment. Like Live And Let Die and The Man With The Golden Gun, Moonraker was inspired purely by current cinematic trends, whereas Bond films in the previous decade had created a whole new sub-genre, with other filmmakers desperately jumping on the bandwagon trying to replicate their huge international success. In the 1970s the Bond series simply followed suit and tried to adapt their stories to current tastes, with varying degrees of commercial success. The story of how Moonraker reached the screen is an interesting one, and worthy of retelling in its 40th Anniversary year. Where all the other Bonds end... this one begins! |

||||

|

||||

|

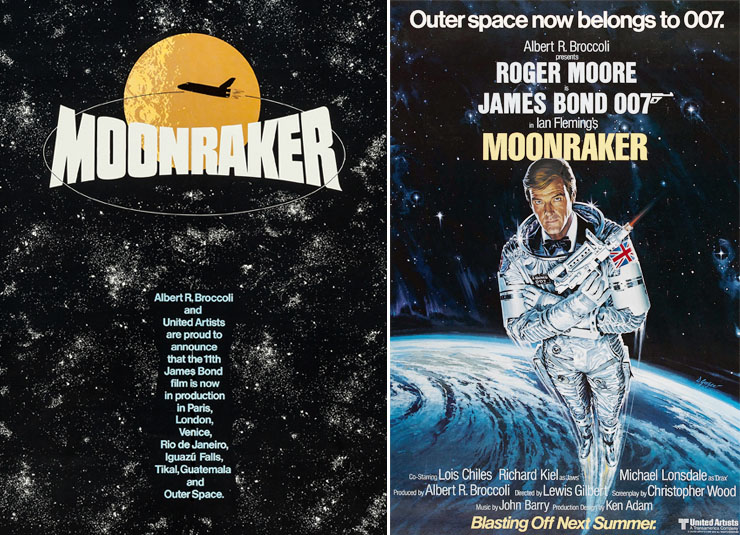

Just after the release of The Spy Who Loved Me in July 1977, pre-production work on For Your Eyes Only began with Lewis Gilbert retained as director. As Roger Moore had originally signed a three-picture deal which had now expired, he started what would become a recurring game of renegotiation, and did not ultimately sign a new contract until January 1978. It was at this point that the decision was made to film Moonraker, and a number of draft scripts were submitted including one by Thunderbirds creator Gerry Anderson, which was loosely based on Ian Fleming's 1955 novel. Three-time Bond screenwriter Tom Mankiewicz also worked on a treatment with director Lewis Gilbert which grounded the story more in science fact than fiction, and hit upon the idea of using space shuttles instead of the single rocket featured in Fleming's novel. Despite his disappointment with the 1954 US CBS-TV adaptation of CASINO ROYALE which tuned James Bond into an American agent, Ian Fleming still had confidence that his novels could be turned into films. Ian Fleming's third James Bond novel had already attracted Hollywood film interest when American actor John Payne (1912-1989) took out an option on MOONRAKER in 1955, with the intention it would be the first in a series of 007 films. Payne ultimately dropped the option, for which he paid Fleming $1,000 a month, once he learned that the rights to the other Bond books would not be available to him. Famed producer/director Alexander Korda (1893-1956) also took out an option on MOONRAKER after reading an advance copy of LIVE AND LET DIE, but ultimately the Rank Organisation failed to do anything with the property and the rights reverted back to Ian Fleming in 1959, becoming one of the package of titles acquired by Harry Saltzman in 1961. In 1978 MOONRAKER was the last Ian Fleming novel available to be filmed by EON Productions, although virtually none of the author's original material made it to the finished film. Beyond its title and main villain in the shape of Hugo Drax, Moonraker shares little in common with the 1955 source novel. The original release posters bore the credit ‘Ian Flemings Moonraker’, but were revised in later printings following objections from the Fleming estate. The amended credit now read ‘Roger Moore as Ian Fleming's James Bond in Moonraker’. |

||||

|

||||

|

Once the story for Moonraker had been finalised, the job of writing the final shooting script was handed over to Christopher Wood, who had co-authored The Spy Who Loved Me with long-time James Bond screenwriter Richard Maibaum. Jonathan Cape published Christopher Wood's screenplay as a novel entitled JAMES BOND AND MOONRAKER, (to distinguish it from Fleming's original) but unlike its predecessor JAMES BOND, THE SPY WHO LOVED ME, this novelization was closer to the finished film, although slightly more serious in tone. Due to the prohibitive taxation then in place in the UK, the decision to make the film in France resulted in Moonraker being the first James Bond film not to be based at Pinewood Studios, although the ‘007 Stage’ was used by the special effects crew to shoot all model work and the climactic space battle. EON Productions signed an agreement with Les Productions Artistes Associes to co-produce the film in Paris, and Ken Adam's spectacular sets utilised every available inch of studio space at Boulogne, Billancourt and Epinay. |

||||

|

||||

|

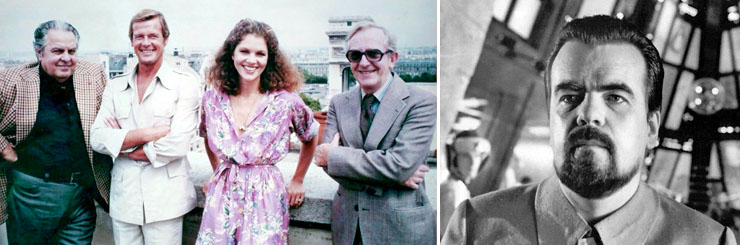

With a script finally in place, casting was completed in mid-1978 with Lois Chiles being offered the role of Dr. Holly Goodhead after a chance encounter with director Lewis Gilbert, when she found herself sitting next to him on a plane journey. Under the terms of the co-production a number of French cast and crew were engaged, and the role of Hugo Drax eventually went to Michael Lonsdale, although Louis Jourdan who would later play Kamal Khan in Octopussy (1983) was also considered. French actor Michael Lonsdale was cast primarily because he could speak English. He had memorably played of Deputy Commissioner Claude Lebel in The Day Of The Jackal (1973), and later opposite Sean Connery in The Name Of The Rose (1986). The role of Corrine Dufour went to French actress Corrine Clery, who had starred in the controversial 1975 erotic drama The Story Of O. Co-producer Michael G. Wilson's Aikido teacher Toshiro Suga was cast as Drax's bodyguard Chang, and Richard Kiel reprised the role of Jaws. Regulars Lois Maxwell, Desmond Llewelyn and Bernard Lee (whose last James Bond film this would be) were also joined by Geoffrey Keen who returned to play Frederick Gray, a role he had originated in The Spy Who Loved Me (1977). Walter Gotell also reprised his role as General Gogol. Both actors would play the same roles in the next four films in the series. John Barry also returned after a one-film absence to provide a memorable score, alongside Shirley Bassey who sang the title song for the third time in the series, after an initial recording session with American singer Johnny Mathis was abandoned. It was intended that Claude Renoir, who had photographed The Spy Who Loved Me would also return, but his failing eyesight resulted in Jean Tournier being engaged as a last-minute replacement. With hindsight, Tournier's lush Panavision cinematography is one of Moonraker's enduring successes, with the slow-motion death of Corinne being a stand-out sequence that is once again at odds with the rest of the film. |

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

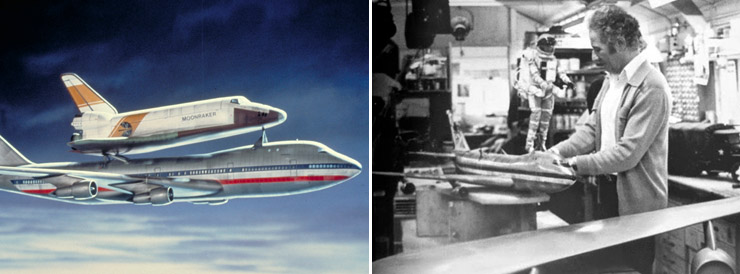

The film starts off well with a first look at Derek Meddings superb miniatures, as a space shuttle being piggy-backed on a Boeing 747 is hijacked and its crew killed in a surprisingly shocking sequence. The opening scenes are accompanied by the welcome return of John Barry's atmospheric music, which was a far cry from the disco-infused opening of The Spy Who Loved Me (sadly all of the music from the Moonraker pre-credit sequence was missing from the original soundtrack album). |

||||

|

||||

|

Producer Albert R. Broccoli had convinced United Artists that Moonraker would require a budget of $32-million, which was more than double what had been spent on The Spy Who Loved Me. The decision to make Moonraker bigger and better than its predecessor, meant the film needed something to top the audacious ski sequence which had audiences cheering in 1977. The spectacular free-fall sequence which opens Moonraker was the first actual footage shot for the film on May 18, 1978, with skydivers B.J. Worth and Jake Lombard making the first of 88 aerial jumps over the next five weeks. The huge popularity of Jaws in The Spy Who Loved Me prompted the producers to bring back the character for the next film, and his inexplicable entrance in the aircraft during the pre-credit sequence of Moonraker is the first of many errors of judgement in the story. This comic performance at the start of Moonraker undermines what had been a well-executed stunt sequence, as the actual free-fall and aerial fight is superbly staged and edited without resorting to too much special effects photography. However, the inclusion of a back-projected Richard Kiel and unconvincing look-alike gives the audience a foretaste of what is to come in the rest of the film. Ultimately Moonraker is a film at odds with itself, with so many well-executed sequences spoiled by the inclusion of juvenile humour or over-the-top comedy tropes. |

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||