| |

23 May 2017 |

|

Sir Roger Moore (1927-2017)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

RIP

Sir Roger

007

MAGAZINE's Luke G. Williams presents his personal tribute to Sir Roger

Moore |

|

|

When you reach a ‘certain

age’ some deaths don’t just cause you to pause and shed a tear, they force

you to say goodbye to something you have, in fact, already lost… namely a

slice of your childhood.

Although James Bond's creator Ian Fleming died a cruelly untimely death

aged just 56, never to really see the global cultural phenomenon his

imagination eventually engendered, the character of 007 himself has forged

a reputation for immortality, an impression reinforced by the fact that –

until Tuesday 23rd May 2017 – death's fickle sickle had failed to land so

much as a glancing blow on the six men, with a combined age of 436 years,

who have thus far inhabited the legendary tuxedo in EON Productions’ 24

‘official’ 007 epics.

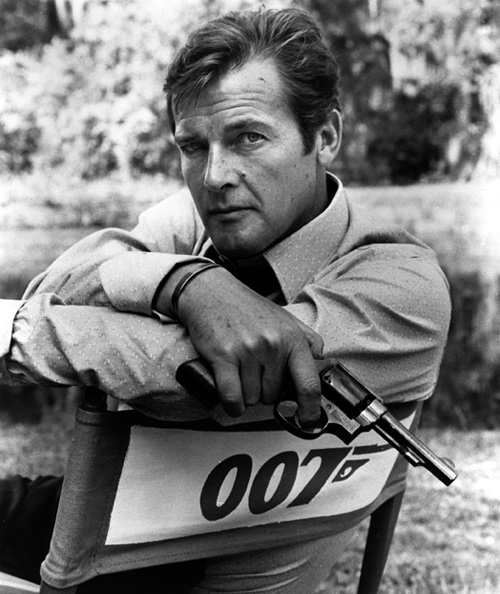

So when Sir Roger Moore passed away this week at the age of 89 it felt, to

me at least, that James Bond 007 himself was perhaps fallible and mortal

after all. |

|

|

Fate would have it that on the day Sir Roger passed I had already arranged

to meet up with two of my closest friends from school, with whom I have

shared a love of James Bond since we first met in 1987.

The sense of shared loss as we sat and chatted was palpable, and not just

in relation to Sir Roger. As a trio we were once inseparable, but these

days, with myriad other responsibilities ensnaring our time, the periods

between our meetings has slowly but inexorably lengthened.

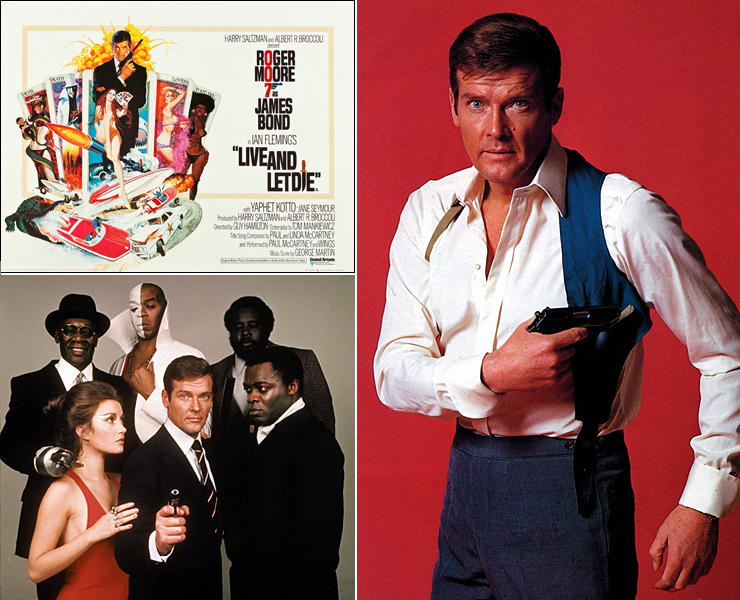

The three of us turned 40 last year, still five years short of the age at

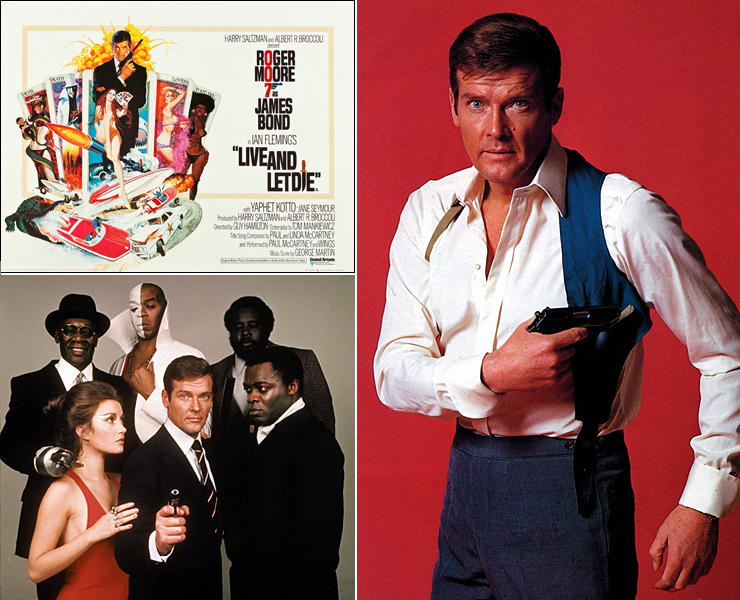

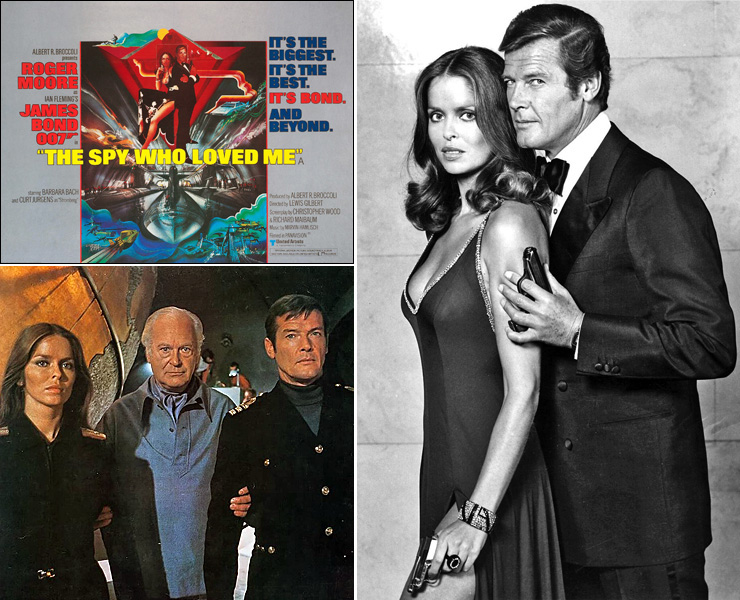

which Roger Moore slipped on 007’s shoulder holster for the first time in

1973’s Live And Let Die, and as we sat in a burger restaurant in

King’s Cross and raised a glass to Sir Roger we reflected with laughter,

joy and real sadness at our memories of a man who truly enlivened our

formative years. |

|

|

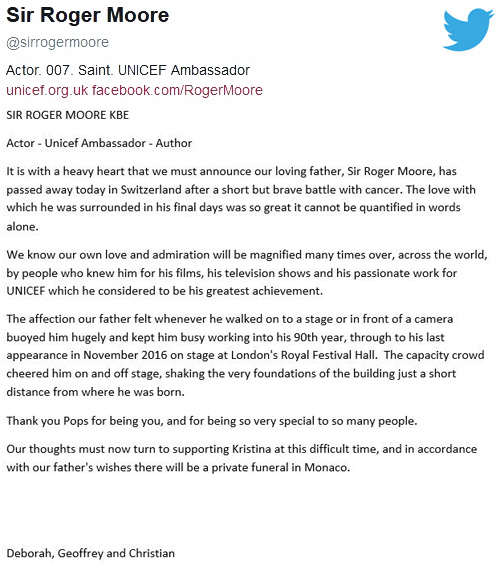

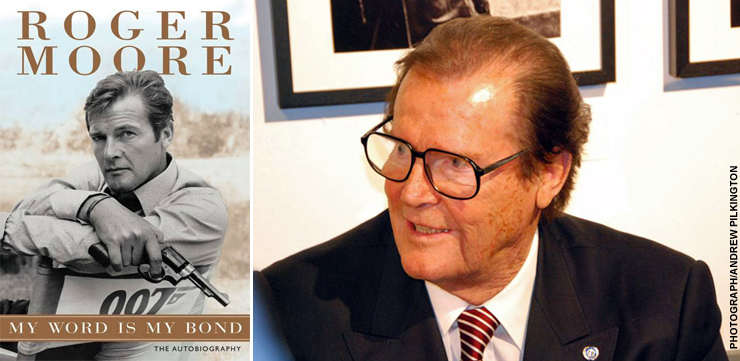

Sir Roger Moore's

autobiography My Word Is My Bond was published in 2008 and

was promoted with a signing at the National Theatre on 16th

October. |

|

|

|

We remembered the time we

listened to Sir Roger interviewed at the National Theatre in 2008 and then

patiently queued to have him sign our copies of ‘My Word Is My Bond’, we

remembered watching him tell pretty much the same anecdotes four years

later at the Rose Theatre in Kingston, and we remembered the joy and

laughter listening to his DVD commentaries had brought us, particularly

when he tried to do an impression of Yaphet Kotto.

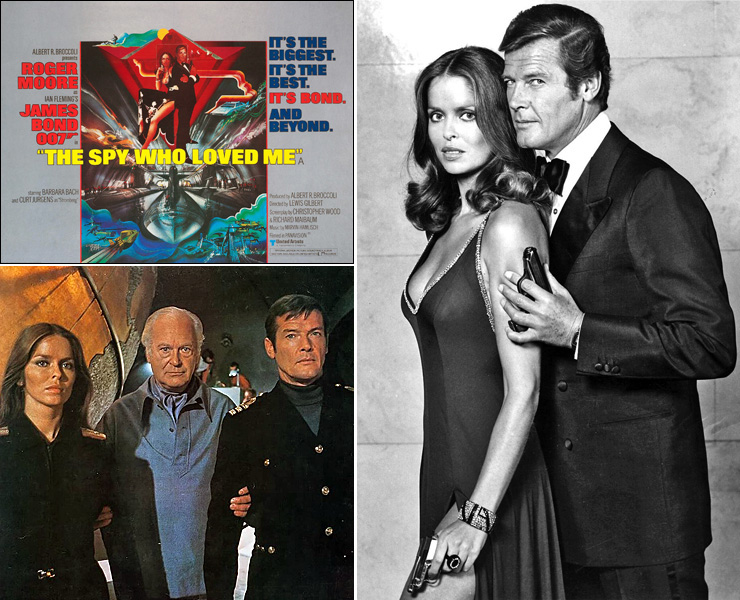

For me, growing up in the drab surroundings of inner-city South London in

the 1980s, the world of Roger Moore’s James Bond, with its colour,

extravagance and glamour provided a welcome escape from the dog faeces

infested streets and urine-soaked council estates of Camberwell that

encircled my own middle-class terraced existence.

Moore was my first Bond, and my early vision of the character was forged

by his style and risqué humour. The first Bond film I ever saw at the age

of six or seven was when ITV screened The Man With The Golden Gun.

Despite being viewed on a tiny colour TV with an irritably erratic indoor

aerial, the film enchanted me with its glamour, glitz and outlandish

flair. |

|

|

When I excitedly sat down to watch Thunderball soon afterwards I

watched Terence Young’s 1965 epic unfold with a sense of bafflement –

where was Roger’s charming and humorous 007 and who was this gruff, tough,

slightly scary 007 who had taken his place?

Although I gradually warmed up to Sean Connery, Moore remained my man,

even if it was a relationship at this stage that was purely consummated on

the small screen.

To my distress, I was not allowed to watch Octopussy in the cinema,

being forced into a re-release screening of The Jungle Book instead

by my over-cautious parents who did not feel I was a ready for a PG

certificate film with a sexual innuendo in its title. It was a minor

consolation that I persuaded my mum to buy several boxes of Shredded Wheat

over the next few weeks, which I dutifully wolfed down despite hating the

taste, in order to collect a series of Octopussy stickers.

When 1985 rolled around, I was finally deemed of age to watch a

PG-certified Bond film in the cinema – it was Roger’s swansong, A View

To A Kill.

In the weeks leading up to the film’s release I was in a fever pitch of

excitement, carefully clipping reviews, photos and a serialization of the

screenplay from my dad’s discarded newspapers and magazines and placing

them in a scrapbook I had bought from Superdrug.

Thrillingly, my dad bought me an official A View To A Kill tie-in

magazine from a newsagent in central London that had a steady supply of

‘American’ magazines and comics. I devoured every page eagerly while the

pictorial of Bond girls in various states of near undress won me some

invaluable playground kudos.

When I finally saw A View To A Kill at the Coronet cinema at the

Elephant and Castle I was entranced from beginning to end, immediately

anointing it as the ‘best Bond film of all time’. |

|

|

Things soon changed though.

My interest in 007 dramatically changed tack after a double whammy on ‘The

Road To Bondian Damascus’ – I began reading the original Ian Fleming

novels around the time that Timothy Dalton was handed Roger’s Walther PPK.

My vision of what made a good Bond film was irrevocably altered. With

typical teenage arrogance and certainty I rejected my previous love of

Moore as youthful folly and his films as slapstick nonsense.

Watching A View To A Kill with fresh eyes on television and video,

I now regarded Moore as one might regard an embarrassing elderly relative.

It was an attitude which seemed to chime with the changing social and

cultural focus of the 1990s and early 00s, in which Moore widely came to

be seen as a something of a figure of parody and a byword for a particular

type of British ‘naffness’, witness, for example, the frequent references

towards him throughout Steve Coogan’s Alan Partridge incarnation. |

|

CONTINUED |

|