|

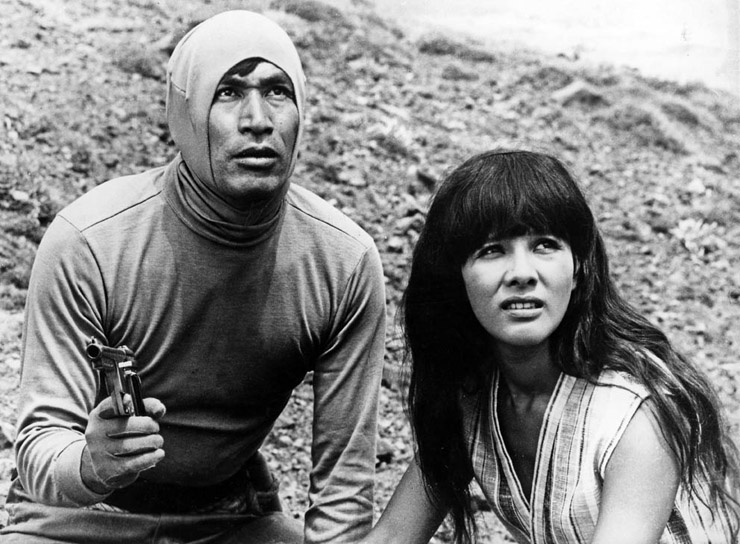

When EON Productions set about casting You Only Live Twice,

Japanese actor Tetsuro Tamba – who had already worked for director Lewis

Gilbert in 1964 drama The 7th Dawn – proved an important sounding

board in selecting Hama and Wakabayashi for the two major ‘Bond girl’

roles in Roald Dahl’s screenplay – Ama diving girl Kissy Suzuki and

Japanese secret service agent Suki (as the character was originally

named).

Subsequently, Tamba was also cast in the film as Tiger Tanaka, a role

originally offered and refused by Toshiro Mifune, an actor renowned for

his collaborations with legendary Japanese helmer Akiro Kurosawa, who

instead opted to appear in John Frankenheimer’s motor racing drama

Grand Prix.

Tamba apparently recommended Hama and Wakabayashi because he felt they

would pick up English pretty quickly, as well as for their photogenic

qualities.

However Hama, who had often agonised during her years in Japanese cinema

about whether to remain in showbusiness, soon struggled with the attention

that being a part of the 007 franchise entailed.

“I had never seen a 007 movie, and had no idea 007 was such a huge

international hit,” she later told the New York Times, revealing

that a member of the studio and production team told her on her arrival in

London: “You’re a Bond girl now. The clothes you wear, the jewellery you

put on, we will manage all of that.”

“Everything from my weight to the height of my heels was decided,” Hama

added. “It may have looked glamorous, but for me, it was all a huge

ordeal.”

These comments echo

Hama’s words which appeared in press materials when You Only Live Twice

was originally released: "I was simply terrified when I was first given

the part – the Bond films are the most popular ever to play in Japan and

all my friends told me that the eyes of the world were upon me. Suddenly

I'm on my way to England to appear with Sean Connery in utter strange

surroundings.”

Today, it is almost impossible to imagine the attention that must have

been lavished on Hama and Wakabayashi when they were cast as Bond girls.

When You Only Live Twice was in pre-production, Bond-mania was at

its height, while Japanese actors and actresses, indeed Japanese culture

as a whole, had enjoyed comparatively little exposure in major Hollywood

films. Toshiro Mifune was a familiar face in Hollywood, and the likes of

Eiji Okada had also made some impact in the West, while Frank Sinatra’s

1965 film None But the Brave – a co-production between Warner

Brothers and Toho – used several Japanese actors – however the 007 series’

incursion into Japan represented a whole new level of exposure and media

attention for the local actors and actresses involved.

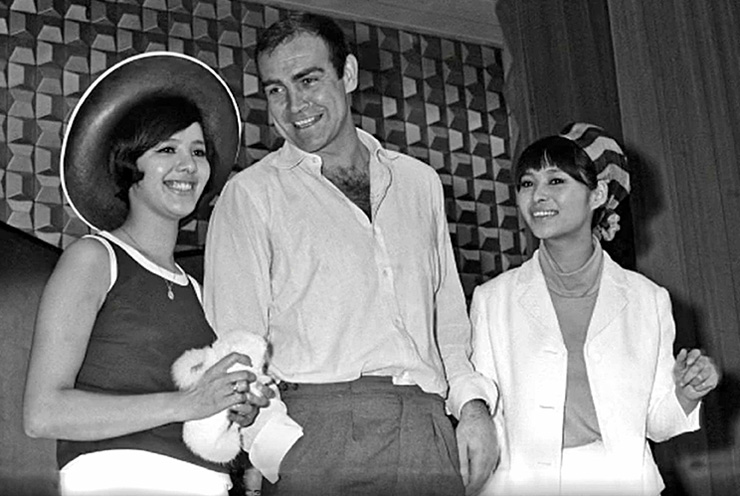

Then, as today, Hama emphasised the support and kindness that was shown to

her by Sean Connery as she dealt with her new-found fame. “I am grateful

to him for his kindness,” she said in 1967. “Although I only understood a

few words of what he said I didn't need language to appreciate his

charming manner."

To the New York Times in 2017 she added: “Every morning, he

[Connery] asked if I was having any trouble. He also had a tough life

before becoming a star, so he understood me.”

Adding to Hama’s unhappiness during the production of You Only Live

Twice was the fact that she struggled to pick up English. According to

director Lewis Gilbert this led to an unexpectedly dramatic situation.

His account of Hama and Wakabayashi’s casting appeared in his 2010 memoirs

All My Flashbacks:

“Two actresses were

chosen after that day’s work in the studio, Akiko Wakabayashi and Mie

Hama. Neither spoke English. The best thing we could do for them, we

thought, was send them to live with two English families where there

were children. Conversation would be non-stop and simple. For three

months the two actresses stayed in England, at the end of which we made

another test, this time in English. My old writing colleague Vernon

Harris, an ex-actor, cued them in. Akiko was fine. She could not only

say the words, she could make sense of them. Mie was another matter. The

three months had evidently been a struggle for her. Firstly, she

couldn’t understand me, and when she spoke she was incomprehensible. She

could make no sense of the dialogue at all. As shooting of the film was

soon to start we were facing a big problem.

I went to Cubby and Harry to explain the hopelessness of the Mie

situation. She would have to go home. “Yes, but how do we tell her?”

they said. It was going to need delicate handling and none of us spoke

Japanese. My suggestion was to ask Tetsuro Tamba. It was the only way

out. He was with us in London and he could talk to Mie.

“Good idea, good idea,” said Harry and Cubby, relieved to be shot of the

problem, not that it was a problem Tamba wanted either. “That’s serious,

very serious,” he said.

“But could you not explain to Mie that it would do her no good to give a

bad performance in a Bond film? It would be bad for us and bad for her,”

I said.

“I’ll take her to dinner,” said Tamba. “I don’t know what I can do but

I’ll try.”

The next morning, I rushed in to see him. What had happened? “Straight

to the point,” said Tamba, “if you insist Mie goes back, tonight she

will jump out of her window at The Dorchester Hotel and commit suicide.”

“What!” I said, “You’re joking.”

“No,” said Tamba, “you have to understand face-saving in Japan. It is

most important. You have a girl who has been sent to England to be in

the biggest film ever made in Japan and everybody in her country knows.

If you send her back, you are saying she is no good. So, for her, the

only way to save face is to commit suicide.”

This was indeed serious, and it was not up to me to make a decision off

my own bat. The producers had to be told.

“What happened with Mie? What did she say?” asked Harry and Cubby when I

went to see them.

“Sit down,” I said. “The news is not good.” Actually I was quite

enjoying myself. The two of them were always dumping problems in my lap.

Now it was my turn to dump a problem in theirs. I told them of Mie’s

threat to jump out of her window at The Dorchester, concluding with, “It

would make a splash in England and an even bigger splash in Japan,”

which I thought was rather funny. Cubby and Harry did not.

“What shall we do?” they asked.

“If Mie does what she says she will do,” I answered, “that’s the end of

the film because you’ll never get to make it in Japan and you can’t make

it anywhere else. It’s that simple. So, we keep her and either carry on

in the hope that her English improves or we revoice her at the end of

the shoot and live with it.”

In the event, several months later, the latter is what happened. Skilled

voice artiste Nikki van der Zyl, who had revoiced other Bond girls,

listened to a Japanese speaking English and came up with an accent that

sounded Japanese but had useful inflections.”

What Gilbert does not

mention, is that the roles earmarked for Hama and Wakabayashi were also

switched to make the filmmakers’ post-synching easier – with Akiko taking

on the more dialogue heavy role of Suki (which was then renamed Aki) and

Hama shifted to the role of Kissy.

Hama herself has never spoken about Gilbert’s claim, although Wakabayashi

did briefly give Vaquer and Homenick her recollections of the casting

switch:

“Of course it was the director's decision. I was given the role of Kissy

after an interview and a screen test in Japan (though it was a temporary

decision). But when we read through the script in London, the roles were

switched round. The name of the role was originally Suki, but it was

changed to Aki as it sounded close to my name.”

Ultimately, Hama’s struggles with English led to her being revoiced, while

Wakabayashi’s voice performance, remarkably – given the fact she spoke no

English when originally cast, and given how often other 60s Bond girls

were dubbed – made it to the final cut.

Like Hama, Wakabayashi spoke fondly of co-star Connery, telling Vaquer and

Homenick: “James Bond in the movie is a ladies' man, but Sean-san is a

warm-hearted, honest man.

He has a clear vision as

an actor. He can be stubborn from time to time, but he is a real man with

a bit of old-fashioned taste.” |