|

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW |

||

|

||

|

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW |

||

|

||

|

|||

|

LUKE G. WILLIAMS in

conversation with Ian Fleming biopic director Don Boyd… With thanks to The Don Boyd Archives; University of Exeter; the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum. |

|||

|

|||

|

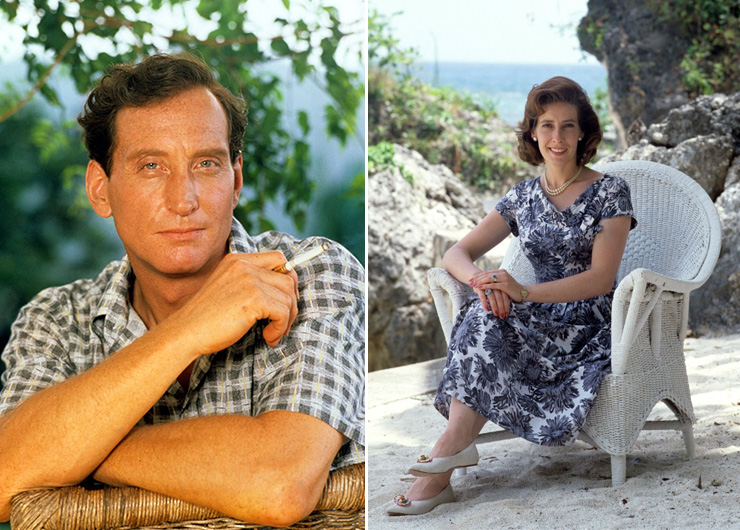

Various versions of the life of Ian Fleming

have made it to television screens over the years, most of them proving

utterly risible (Spymaster starring Jason Connery and Fleming:

The Man Who Would Be Bond with Dominic Cooper immediately spring to

mind as being particularly terrible). A notable exception is Don Boyd’s 1989 Anglia TV film Goldeneye – the first televised biography of Fleming and far and away the best. Based on John Pearson’s 1966 official biography of 007’s creator, Goldeneye boasts an excellent script by Reg Gadney, a compelling central performance from Charles Dance as Ian Fleming and a strong and accomplished supporting cast, including Phyllis Logan as Ann Fleming and Julian Fellowes as Noël Coward. It also benefited from filming on location at Fleming’s house – also named ‘Goldeneye’, of course – in Oracabessa Bay, as well as at other Jamaican locations, lending the production an extremely authentic and exotic ‘big screen’ look. Having enjoyed Goldeneye very much when first watching it on ITV as a young Bond enthusiast way back in 1989, it was with delight that I was able to watch it on the big screen 11 years on – and a great pleasure to interview director Don Boyd a few weeks later. Don is a very affable man and, as is clear from the interview that follows, his passion for the work of Ian Fleming is both infectious and inspiring. |

|||

|

|||

|

Originally, I recorded Goldeneye

from TV on a Betamax video, which I lost years ago, so it was a delight to

finally see it again. How did the whole project come about and where did

your interest in Fleming come from originally? Well, my interest in Fleming is very easy to identify. I absolutely adored all his books when I was a boy. I used to sneak copies of the Bond books into my dormitory at boarding school and read them late at night. There were about three or four writers that wrote, well, the term pulp fiction is unfair really – but Mickey Spillane, Eric Ambler and Ian Fleming were – I suppose – a group of people who wrote books that weren’t erudite literature but they were extremely entertaining books that as a reader you really enjoyed. They also had huge intelligence behind them, and that’s what I was drawn to with Fleming. I loved the books and bought them all. Interestingly enough, I saw my first Bond film at a huge cinema – what used to be known as the London Pavilion Cinema in Piccadilly Circus. I certainly remember seeing the first one that was made into a movie there, which was Dr. No and, of course, as you know, we ruthlessly parodied the moment where Ursula Andress walks out of the sea in our film in a rather romantic way, which I liked very much. Anyway, going back to your question; Fleming was an intelligent man writing about a character that had glamour and intelligence. Bond was also vulnerable and there were all these exotic locations in the books, which appealed to me as I’d been brought up in a pretty exotic way. For example, I lived in China, America, Uganda, and Kenya – and so, to a certain extent, I rather identified with this man who was always dotting around all over the world. The idea of a secret agent with a ‘licence to kill’ was also very exciting. You knew that at any moment Bond might kill somebody. I loved the writing of F. Scott Fitzgerald and in The Great Gatsby used to like the idea that the main character was somebody that might have killed somebody in the past. Well, in Bond’s case you know he has killed and has a licence to do so too! I was such a Fleming fan that later, when I had made a movie, I bought first editions of every single Fleming book. |

|||

|

|||

|

That was a wise investment! It was indeed! Later when I needed some money I sold them for a very big profit. I even had a copy, which we used in the film, of Birds of the West Indies, [by the American ornithologist James Bond, one of Fleming’s favourite books]. The other thing, of course, about the Bond books is that there was sex in them and there were girls, glamorously described! For a boy in his teenage years that was very exciting! I was at prep school when I read my first Bond book. So I was about 13. I particularly loved CASINO ROYALE. If you want my opinion, that is the best of all the books. I think I agree with you on that. Oh you do? I love that book. When was it published – 1950 [1953] or so? I was horrified at the [1967] film version which I thought was not funny at all – it was supposed to be funny. It didn’t take the book seriously. The Daniel Craig Casino Royale I rather liked. Me too. I thought it was pretty cool. I thought it had a little bit of a cheesy ending but it kind of worked. I thought Daniel Craig was brilliant in it and had a kind of dark, witty side to him that was very much a Bond I could identify with. But the old one? That was a mess! It was the first time I was disappointed by anything relating to Bond. |

|||

|

|||

|

So how did the idea of dramatising

Fleming’s life come about? Partly from the Bond books and my enthusiasm for them, but it didn’t all come together until I met [Fleming’s original biographer] John Pearson, albeit in a completely different context. John had written a book called The Profession of Violence about the Kray brothers. I came to meet John in an interesting way through [film producer] David Puttnam, who had heard I was interested in the Krays’ story. Puttnam also introduced me to this very interesting character called Gilbert France, who knew the Krays. Gilbert invited me for lunch and showed me a letter which said: ‘Dear Gilbert, can you get hold of David Puttnam; what has happened to the film?’ When I looked at the top of the letter it said, ‘H.M. Prison Broadmoor’ and it was signed ‘Ronnie Kray’! That began a whole process which led to meeting the Krays and dealing with the criminal world for about six years. I owned all the rights to that book with Roger Daltrey. Anyway, John and I immediately got on and we became great friends. One day he said to me: ‘Don, have you read my book about Ian Fleming? I knew him well.’ I said: ‘No, please get me a copy!’ Once I had a copy I wolfed it down and I immediately thought: ‘Wow! This would make a tremendous film!’ John gave me an option on the rights, we made a deal and that began a whole new saga. I created an early scenario for the book. I definitely saw it as a movie, not as a television film. I wanted to direct it myself and I had sort of begun to return to my directorial career after having spent quite a lot of time producing. For example, I was producing Derek Jarman’s War Requiem – the Fleming project was so different and so exciting! |

|||

|

|||

|

Something that certainly struck me,

looking at your résumé, were the huge contrasts and versatility in your

career – from Derek Jarman and Alan Clarke to Ian Fleming is quite a leap!

God, yes! Goldeneye was a totally different project, but it reflected the incredible enthusiasm that I had for this extraordinary man, Ian Fleming. I did a lot of research on his career, his life and times, including his banking career. I also read his brother Peter’s books, which were marvellous. I’ve read a couple of them too – Peter Fleming was an excellent writer. They’re good, aren’t they? I particularly enjoyed and identified with the one set in China [One’s Company: A Journey To China In 1933], particularly as I had been there and knew the country well. Anyway, after optioning John’s book I did the usual rounds trying to get people interested. At the time I had a very good relationship with Harvey Weinstein. Harvey had made his first real chunk of money out of a movie I had made, called Aria. He looked at Goldeneye and wanted to find some other director for it – he made a lot of wrong suggestions! After that it somehow got into the hands of two guys who were salespeople for The Muppets and had a very big link with the people at Anglia – a guy called Tim Buxton. They read it and said: ‘Don, forget it. Don’t think about it as a movie. We’re about to set up a ‘movie for television’ division and we want to make this one the first one.’ Anglia liked the book, they liked the material I had written and I said to them: ‘Look, I’m going to want to have this written as a script’. I’d already identified Reg Gadney as a possibility for writing it. I knew his novels. He was intelligent and he’d been in the intelligence services, so there was a parallel there, and Reg and I got on like a house on fire. He’d also written a biopic about the Kennedy's which Anglia loved. All this coincided, by the way, with some sensational reviews for War Requiem – Variety reviewed it well, for example, and it was also very well-received in the press and that helped my cause in the strange process that happens in these situations. Eventually, Graeme MacDonald at Anglia told me: ‘We’ll do it, we’ll back it. You don’t have to worry.’ And he did! He completely honoured every promise he made to me. We assigned Brenda Reid to it as producer, she was an ex-scriptwriter at the BBC who knew Reg. Then Reg and I then began writing the script and didn’t stop working on it until it was finished. It was a very happy relationship. |

|||

|

|||

|

From the initial meeting with John

Pearson and that initial conversation, until Goldeneye got on to TV

screens, what was the timescale? I’d say quite a long time – probably several years. But one thing I ought to say is that what John did, is he opened up a whole bunch of research that proved very valuable. For example, he arranged for me to meet Peter Quennell, who was a great friend of Fleming’s. He really opened up about Fleming. I met [Fleming’s widow] Ann, who was still alive at the time. She was terrific and very sweet and sort of very pleased I was going to represent her in this. I also met Kingsley Amis through Peter Quennell. There were various other people that John knew that I met that had anecdotes about Fleming; some of them were useful and some of them weren’t. It wasn’t just a question of reading the book – there was a whole research process that I followed as a result of John Pearson’s knowledge and his contacts. |

|||

|

|||

|

From meeting people who actually knew Fleming, what was the impression

that you gleaned of him? First of all, he was quite a moody bugger! A very moody man who was very difficult to second guess and didn’t suffer fools gladly. He was the sort of man that – I remember Quennell saying this – would take a look at your shoes and decide something about you from your shoes! It wouldn’t necessarily mean they had to be highly polished but I got the impression that he was a man who was interested in detail and how people were. He was very old Etonian in that way. I got the impression that he was a complex man, but he also didn’t have that annoying ego that a lot of people who have had a lot of success have. He didn’t place himself on a pedestal in the way that people who become famous often do. I really liked that about him. There was one Fleming quote that I remember to this day that I really loved that somebody told me – it may even be in the Pearson book; Fleming said something along the lines that all men were equal and he hated words like “genius”. He said: ‘I’ve only had two heroes in my life. One was God and the other was Winston Churchill!’ He kind of revered Churchill, for obvious reasons. Fleming clearly had quite a humanistic view of people – he was somebody who was very famous, but somebody who wasn’t famous was still on an equal basis as far as he was concerned. I got the impression that he liked to meet people that weren’t necessarily famous. He moved in the circles of high society London, but, like Bond in the books, remained outside of everything. Despite his naval intelligence background, I think Fleming was an outsider rather than an insider. In that respect there was a very strong and obvious correlation between Fleming himself and James Bond. He wrote himself into that character. I also think Fleming was a romantic man and he also shared something I love, which is golf. In terms of the danger in the Bond books, I think a lot of that came from his imagination. He also had a very witty ability to think up ridiculous schemes, which he took extremely seriously. For example, the scheme he had about poisoning [Fidel] Castro [which he famously shared with the Kennedy brothers] was a completely seriously thought out scheme. I think Fleming was amazed at the kind of interest that [President John F.] Kennedy had in his books. But you can see why Kennedy did like them, because they were such a good read. Something else I loved about Fleming was his clear enjoyment of his house, ‘Goldeneye’. It was a very deliberately isolated set-up that he created in Jamaica. Fleming was a loner. He bought a house that was like a chapel and lived in an almost monastic way, away from the usual bullshit that lots of upper-class people surround themselves with, in their big country houses. That was very intriguing, because it was clearly a very deliberate decision by Fleming. |

|||

|

|||

|

In terms of the scripting process that you alluded to earlier… am I

correct that you formed an outline and then a draft script which you

worked on with Reg Gadney? Yes, I did an outline, although I didn’t bother giving myself a story credit. Reg read the outline and liked it very much and he and I made an agreement – I said to him: ‘Reg, I want you to understand that we need to do this together. I don’t want to take any credit or anything like that, but we’ll do this together.’ So we had months of amazing research, literally laughing on the floor over some of the jokes and ideas we came up with. Reg had the same enthusiasms as me and he had an inside knowledge of naval intelligence. Reg was older than me. He also shared something Fleming had, which was he was completely, utterly anarchic when it came to social stuff. He lived on his own in a small flat and he kept himself away from the literary world. He had been in the art world before as one of the head honchos at the Royal College of Art, and he draws beautifully. We went through quite a few drafts but only because he and I wanted to alter things, not really as a result of notes we got from anybody else. Producer Brenda Reid was immensely helpful and would say: ‘I think you should think about this or that in structural terms.’ But she didn’t interfere with the scenes. She loved the script from the day that she saw the first draft. Then we began the casting process. Quite quickly we considered Jeremy Irons for Fleming and I dropped Jeremy a note. I know Jeremy and I said to him: ‘What about it?’ But his agent said: ‘No, he’s just not interested in playing Fleming.’ My second idea was so simple – I said to Reg: ‘It’s Charles Dance.’ He said: ‘You’ll never get him.’ I said: ‘I bet you we do.’ So I sent Charlie the [Pearson] book; I also sent him some planning material, I think, and he accepted. By the way, he was knocked out watching the film that day [at the BFI]. |

|||

|

|||

|

That’s fantastic! Yes, he sent me a beautiful letter saying how much he loved the film. It was a really beautiful letter. Charlie later told me he was nervous [during the casting process] because he really wanted the job. We really wanted him. I knew what I could get from Charlie, which I did, which was that dark, brooding and slightly self-deprecating, witty side to him, which Fleming also had. We talked about that a great deal and I spent quite a lot of time with Charlie talking about the character and getting him to meet people and getting him involved in the characterisation. The only thing I didn’t get to do with him was to get to ‘Goldeneye’ itself before filming. It’s turned into a resort now, but back then it was literally exactly as when Fleming had lived there. I wrote to the owner Chris Blackwell and said: ‘Can I rent it?’ Before filming I made two trips to ‘Goldeneye’ – one of them was with Robert McCrum, the literary editor of The Observer, who at that time was the head of Faber & Faber and was a very great friend of mine. We went there in the spirit of being in the house of Fleming and Robert did some writing there. All the scenes that we filmed at ‘Goldeneye’ stemmed from my experiences there; swimming and reading the Pearson book. Fleming was so romantic about Jamaica and ‘Goldeneye’ – that place was his paradise. It was a crucial part of my writing process. Reg didn’t get the privilege of going until we were shooting. I’d love to have taken Reg beforehand but it was enough that I’d been there. |

|||

|

CONTINUED >> |