JAMES BOND

|

||

|

||

JAMES BOND

|

||

|

||

|

||||

|

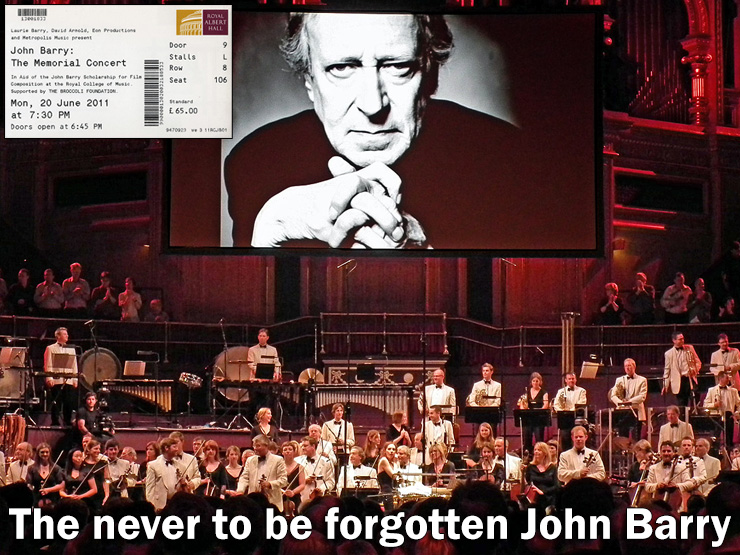

Monday 20 June 2011 will forever be remembered by all who were in attendance at the Royal Albert Hall as a truly magical evening; for it was on this evening, in that place that the worlds of music and the movies united to pay fulsome tribute to the finest film composer to ever draw breath - John Barry Prendergast. LUKE WILLIAMS' personal and poignant report perfectly captures the emotional ambiance experienced by many at 'John Barry - The Memorial Concert'. |

||||

|

John Barry supplied the soundtrack to my childhood. It was his music I played endlessly on my father's ageing record player on long rainy Sunday afternoons while I pretended to labour over my homework. It was his music I played on my yellow Walkman while sitting on the back-seat of my mum's car as it carried me on epic journeys to visit my grandparents or the seaside. And if my homework ended up unfinished and I got shouted at by a teacher on Monday morning, or if I ended up sitting in the car for hours on end in a motorway traffic jam, then it didn't matter...because in the company of John Barry's music, I was never alone and I was certainly never in drab, grey inner-city Camberwell, or on the rear seat of an uncomfortable Citroen 2CV... no, in the company of John Barry's music, I was transported to glamorous 1960s London, or the exotic interior of an Aston Martin DB5... |

||||

|

I guess that's why, in January this year, when I heard that John Barry had died, I felt that a little piece of me had died with him. And so it was that I found myself on iTunes downloading digital versions of the vinyl Long Playing record albums I still own (but can no longer play because my father's ageing record player has given up turning, even though it remains, a sentimental relic, on a shelf by my bedroom window). And so, with the best of John Barry's work safely downloaded on to my iPhone, once again, I returned to his company... I sat at work with my headphones on listening to Bond songs, I sat on the bus listening to the Midnight Cowboy theme and I sat at home writing articles for 007 MAGAZINE while listening to The Persuaders theme, The Ipcress File and those peerless 11 James Bond soundtracks...and I soon realised, with relief, that a little part of me hadn't died, but had actually been brought to life again. I also realised, with growing astonishment, that unlike some enthusiasms from childhood that in the cold harsh light of adulthood seem embarrassing, John Barry's music, will never be diminished or passé - to reference one of his own favourite sayings - “what is romantic is imperishable”. |

||||

|

||||

|

That's why, on Monday 20 June, nearly five months after Barry's passing, I joined several thousand other fans in making a pilgrimage to the Royal Albert Hall for a special concert in his memory. I took my seat high up in the gods, and I sat, mouth agape, a boy again, as performances of his greatest compositions by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra flowed from the stage, interspersed with personal tributes and reminiscences from his many friends and admirers, and I watched, as fascinated as when I first saw them, as clips of Barry being interviewed on BBC TV's OMNIBUS programme played on a giant video screen. |

||||

|

After Sir Michael Parkinson placed Barry and his work into the context of the “magic roundabout of the 60s” and a welcome message from Barry's son Jonpatrick, the Philharmonic, expertly marshalled by renowned conductor Nicholas Dodd, began their evening's work with a dynamic instrumental version of Goldfinger (how, how, how did that song and score not receive an Oscar nomination or award? I found myself reflecting yet again, a question for which there is no possible answer that could ever satisfy me). Stirring and scintillating renditions of the main themes from Zulu and The Ipcress File followed, then Born Free and Midnight Cowboy, the latter accompanied by a wonderful harmonica solo by Julian Jackson. Classic melody followed by classic melody and every tune, every note, every chord touched me, moved me, penetrated my mind and fed into my very soul... As well as the tunes there were the tributes; Barry's great friend Sir Michael Caine, unable to attend the evening in person because he “didn't want to offend Batman” (Caine is currently working on Christopher Nolan's third 'Bat-feature' The Dark Knight Rises) appeared on screen and, with typical class and warmth, re-told the familiar tale of how he was staying at Barry's house during the 1960s and was kept awake one night by Barry working on a composition on the piano - the next morning Barry revealed what he had written, unbelievably, absurdly, in the space of just one night - the theme to Goldfinger. “I was the first person in the world to hear Goldfinger," Caine recalled. "And I heard it all night.” I sat and I laughed, despite the fact I've heard or read the anecdote numerous times before, and my heart, the Albert Hall's heart, ached when Caine's voice cracked with genuine emotion... |

|||

|

But then I was laughing again as lyricist Don Black entertained the audience with his wit and warmth, explaining how: “John Barry changed my life with a sentence... “Do you fancy writing something called Thunderball?” Just as John Barry transported me regularly out of Camberwell, so Black claimed that it was this offer that “got me out of Hackney”, while also admitting, in a nod to Barry's legendary love of a tipple that “I remember the lunches [with John] more than the songs.” |

||||

|

||||

|

Just once was the magical spell broken, and I feel rather churlish to even mention it, when the first half of the concert ended, literally, on a sour note with Rumer's disappointing rendition of 'We Have All The Time In The World', which was off-key in more than one way. But the second act soon wiped away any such negativity as a seductive solo saxophone by Nigel Hitchcock of Barry's Body Heat theme and a romantic and lush rendition of Out of Africa reminded me, and the whole audience, of Barry's astonishing musical versatility. And then came the final 40 minutes, and once again I was a child; 007, my 007, Timothy Dalton strode on stage and spoke (why oh why did he only make two Bond films? I found myself reflecting yet again, a question for which there is no possible answer that could ever satisfy me). Dalton's voice, that wonderful sonorous voice, heavy with emotion, recalled Barry as a “kind and generous man” before reading a passage by priest and poet John O'Donohue that Barry had kept on his desk and was "very dear to John's heart." O'Donohue's poetic sentiments were lent extra weight by Dalton's soulful, mournful Shakespearean timbre, and as he spoke the line “May the sacredness of your work bring healing, light and renewal to those who work with you and to those who see and receive your work” everyone present knew exactly what John Barry had meant to them, be it personally or professionally, or even as an unknowable, unreachable name on a film credit or album sleeve. |

||||

|

||||

|

Another person to whom Barry meant so much, five-time Bond composer David Arnold appeared, a guitar draped around his neck. Arnold spoke simply and without affectation of the dramatic effect Barry had had on his life and career: “I heard John Barry and wanted to be a film composer.” His solo performance of a little-known late Barry composition, ‘Tick The Days’, resonated with love and admiration for his musical mentor, achieving a level of sincerity that was extremely poignant. But before things got too poignant, too downbeat, a suite of instrumental Bond themes from the Connery and Lazenby era exploded into life, drawing ecstatic applause from the huge audience, and transporting me, once again back to my childhood, and the days when I'd stayed up late most week nights endlessly re-watching old Bond movies on the Betamax video player I somehow persuaded my mum I should be allowed to keep in my bedroom. Sir George Martin then appeared on stage and spoke of Barry's “unerring instinct for what a film needed” and how tough it had been to follow in his friend's footsteps when Sir George was hired in 1973 to score Roger Moore's debut Bond film Live And Let Die. Like everyone else who spoke, his words ached with love and yearning for a friendship curtailed, a master no longer present. |

||||

|

And suddenly, from nowhere, amazingly, perfectly, there was Dame Shirley Bassey, 74 years old apparently, although she looked decades younger and the power of her voice and drama of her storytelling were undiminished by time or its vagaries - ‘Diamonds Are Forever’ and ‘Goldfinger’, songs which she must have performed thousands of times, songs which in lesser hands can so easily lapse into cliché or parody, seemed as fresh, vital and dynamic as when they were first written. The crowd erupted into applause, Barry's widow Laurie thanked us all, there was more applause, and then it was over. |

||||

|

||||

|

But as I left the Royal Albert Hall I realised, we all realised, that Barry may have left us but his work remains as “imperishable” and inspiring as ever. Walking through the rain and darkness to South Kensington tube station, dazzled, dazed and drained, those magical tunes continued to reverberate throughout my consciousness, tunes which I will never forget as long as I live, tunes which cinema and music lovers will never forget so long as the cinema and music exist. David Arnold's words also echoed through my mind, an epitaph that I will treasure; he put it so perfectly you see, when he described how John Barry is with us now and always will be: “He's in the horns, he's in the trumpets... and he's definitely in the bar.” |

||||

|

PHOTOGRAPHS/GEOFF LEONARD |

||||