|

|

John Grover worked in the editing department for six of the seven James

Bond films released between 1977 and 1989, graduating from assistant

editor on The Spy Who Loved Me, to assembly editor on Moonraker

and then ‘lead’ editor on For Your Eyes Only, The Living Daylights

and Licence To Kill as well as ‘supervising editor’ for

Octopussy.

007 MAGAZINE chief writer LUKE G. WILLIAMS spent an extended afternoon in

John’s entertaining and warm company at his Buckinghamshire home in 2011,

and we are now delighted to publish their full and frank conversation for

the first time… |

|

|

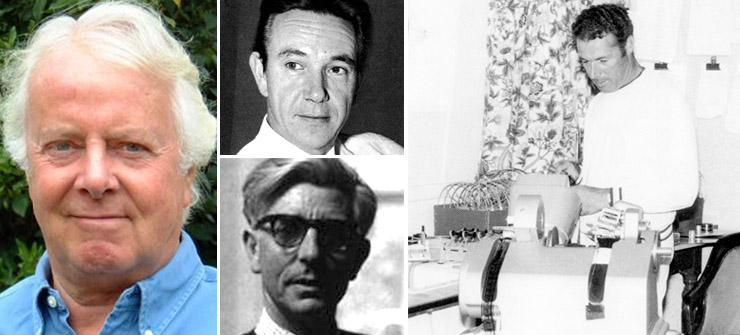

ABOVE: (left) The

MGM Studios Borehamwood clock tower demolished in 1973. The 1967

spoof James Bond film Casino Royale was filmed partly at

MGM Studios in 1966. Among those sequences filmed at the studio

were the Ken Hughes directed Mata Bond scenes in East/West Berlin

(top right & bottom centre [with Joanna Pettet and Bernard

Cribbins]). Filmed partly on the largest exterior

standing set at MGM, which had originally been constructed in 1964

as a Parisian suburb for the second Pink Panther film

A Shot

in the Dark, starring

Peter Sellers as the bumbling Inspector Clouseau. (bottom right) Woody Allen's firing squad scene was filmed on the

French village standing set originally constructed for Eye of

the Devil (1966), which had co-starred

Deborah Kerr and

David Niven. The same set would also later appear in the classic TV

series The Prisoner starring Patrick McGoohan, and can be

seen in the episodes ‘The Schizoid Man’, ‘A. B. and C.’ and

‘Living in Harmony’. |

|

|

|

Can you explain how

you got involved in the movie business?

I had to do National Service when I left school, and when I came out, I

did not want to follow my family into a profession. I was quite

well-educated but I wanted to do something that was more interesting. I’d

enjoyed taking black and white photographs, processing, and that sort of

thing, and I had an uncle whose name was Frank Clark, who was supervising

editor at MGM at Borehamwood. Well, I lived in Norwich, but I had a

grandmother who lived in Palmers Green, so I went and stayed there and got

a job at MGM. From there I was a numbering boy for two years. Numbering is

the lowest grade in the cutting room, it’s where you get the film in and

you put rubber numbers on, it doesn’t happen nowadays.

Then I became a second assistant, with Frank and then later with Ernie

Walter, then I became a first [assistant] and then assembly editor. I did

a lot of pictures with Ernie and travelled the world with him. Had a lot

of fun, went to Israel during the war, which was very interesting. I was

never really or very rarely out of work and got in with John Glen on a

picture that was shot in South America, Murphy’s War (1971). I got

on quite well with him and that’s how I started on the Bonds – which is

what you’re really interested in! |

|

|

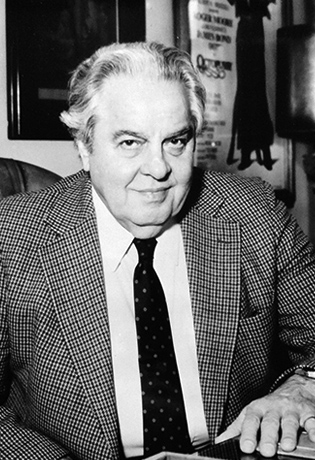

ABOVE: (left) John

Grover. (top centre) Doctor Zhivago editor Norman Savage

(1930-1973). (bottom centre) Sound Editor Winston Ryder

(1915-1999). (right) Editor John Glen at work on Murphy's War

(1971). |

|

|

|

What are your memories

of working on David Lean’s classic Doctor Zhivago as an assistant

editor?

That was when I had just got married, we’d bought a house, so we joined

the picture in Spain. I was on the sound with Win Ryder, Norman Savage was

the editor; Norman has died unfortunately and Win too so, unfortunately,

I’m the only one left. There are very few people left from Zhivago

now. That was a fantastic experience working with David Lean, of course it

was, but it was bloody hard work! He didn’t suffer fools gladly; we did

all the work in Spain and then we were shipped to America where we did the

post-production at MGM in Culver City. That was the start of my period

working either in England or Los Angeles. I got on very well with Mel

Chamberlain who was head of post over there. In fact they tried to get me

to stay over there, they poached people all the time, like they normally

do, the Americans! But my wife was very pregnant by then with my son and

she wanted him to be born over here, so we didn’t take that option up.

So I came back to England and finished Zhivago. We went to the

premiere. It was fantastic but it was hard work, every day, seven days a

week and we were in Los Angeles for probably seven months. The film was

much too long at the first opening, so we then had to re-cut, and shorten

the whole thing. After the premiere we had Christmas over there, we then

cut the picture again, or Norman did, and we had to re-dub it, of course,

so we stayed out there. It was very exciting, a terrific time.

What was next for you after Doctor Zhivago?

We came back here, and immediately I went on to… was it 2001 or

Grand Prix? I can’t remember which one. Let’s see – 1966 was Grand

Prix with John Frankenheimer, that was exciting, because of all the

motor racing with miles and miles of 65mm film, so that was a really big

logistical problem in the cutting rooms, with all the numbering and the

labs. I was once again taken back to Los Angeles to finish the picture

over there and dub it. I was on the picture with Fritz Steinkamp and Stu

Linder who got Oscars, I didn’t but they did, which was terrific for us,

and we got an Oscar for our sound editor [Franklin Milton] too. |

|

|

What was Stanley

Kubrick like to work with on 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)?

I’ve been asked that question many times! What did I think of Stanley

Kubrick? Well, the only time you were allowed to talk to him was when he

invited you into his inner sanctum. He would always be wearing his blue

suit. I was called in there one day because I was doing all the breathing

in the space suits. He would call me into the office and say: “this is

what I want you to do, I want you to wear the helmet and see what you come

up with”. So it would take two or three days in the theatre to shoot it,

then I’d go back, and synchronise it all. We shot on two lots of 35mm so I

could take the noises out because every time you moved you’d be hitting

the microphone, and you’d have to take out all the wheezing and sniffles

and all that sort of junk had to come out because it was just breathing he

wanted. Then I’d have to go with Win Ryder, who oversaw the sound, and sit

there with Kubrick in the theatre and run it. And he would never tell you

what he wanted – at the end of it he’d just say: “thank you John, OK,

let’s try it again”.

My theory is what he was doing was playing for time, for ever and ever. I

mean for six months I did this and each time I tried to make it different!

In the end it was a mixture of bits and pieces from each version.

Everybody says he was brilliant, of course. To me he was a very private

person. I’m not sure he always knew what he wanted, but if he had enough

things shown to him, he knew what he liked. He was clever. His death was

another loss we’ve had.

How did you first meet John Glen and work on the Bond films?

I’d done some assembly work for John and he liked me or liked what I’d

done. So he asked if I would like to come on The Spy Who Loved Me.

It was the opening sequence he was doing; he was going to be in Canada on

Baffin Island, and he wanted me in England to look at all the stuff and

report to him. After he’d shot it, he came back and he’d got that

absolutely wonderful shot of the parachute opening. I was his first

assistant. I didn’t go to Sardinia, but I went to some of the locations,

where he took the cutting rooms, locations where we normally had three or

four weeks. I did more locations on Moonraker, it was shot in

France, so we were in France all the time and I went to Venice. And on the

other Bond films I went to Corfu and Mexico – all over the world!

Absolutely terrific it was too! |

|

|

Albert R.

‘Cubby’ Broccoli (1909-1996) |

|

|

What was your opinion

of ‘Cubby’ Broccoli?

The first time I met him, he was a very impressive man, very big, very

large, very friendly, very jovial and – like most Americans – very good

with names! He always remembered my name which is flattering. He evidently

thought I was okay because I stayed with him and his family for a long

time. He was a lovely man and his wife was superb and very, very kind to

my wife. They got on well.

Cubby would usually come in every day to see the rushes. He was very much

a hands-on producer. If there was a problem, you could go to him. He was

unwell when we were in Mexico working on Licence To Kill – it was a

hard place to be. He had chest problems. So we used to send rushes up to

him In Los Angeles. If he didn’t like something, he’d tell us. He was very

direct, a good producer, a proper producer. There’s a lack of them now!

Cubby had a good sense of humour and would often deliberately sit me next

to the most controversial person at dinner in the green room at Pinewood.

There was this one American feminist I sat next to once. She challenged me

as the editor of Licence To Kill. She started talking to me about

what I thought about women in Bond films and why was it all ‘tits and

bums’ and I said because tits and bums are lovely! It was difficult

sitting with her! She was complaining about the sequence when Bond was

fondling for Pam’s gun, she was saying it was a sexist thing that you’re

showing her knickers! But that scene was fun! It was a good sequence! They

were good together there Tim and Carey! |

|

|

Your view of John Glen? And what was he like to work with?

He’s a superb second unit and action director, sometimes not terribly good

with people, artists were put on the picture and they played themselves…

Actually, maybe that’s a bit unfair to John, because Bond films were very

difficult because of time schedules. I mean they’re huge productions.

Massive. He delegated a lot, which was good, sometimes he upset people on

the set, which he’s allowed to do – he’s the boss!

John would come into the cutting room, not every night but whenever he had

time – purely because we needed to get stuff approved because we had such

a tight schedule. His favourite question was: “what else have you got?”

That’s what happens with most directors. Today working [on computers] it’s

soul destroying because you keep every single version you do and, in the

end… you don’t know what’s good! “Put it back the way it was” is a good

expression, because the first assembly that anybody makes is always the

most difficult. To try and tell a story as it was written in the script,

to try and get it grammatically correct and running comfortably is the

challenge, but after you’ve done that, then it’s easier to speed it up.

The key is to show everything in a dialogue scene and then start deleting

stuff. Don’t ever delete stuff before the director sees it though! That’s

not my job – that’s his job! |

|

|

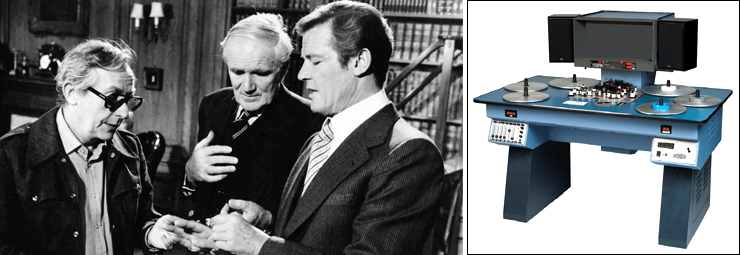

ABOVE: (left)

Moonraker (1979) - Director Lewis Gilbert, Desmond Llewelyn

(playing gadget master Q) and Roger Moore as James Bond rehearse a

scene on the M's office set that was shipped to Paris for filming.

(right) Founded in Germany in 1931, Steenbeck is a brand

name that has become synonymous with a type of flatbed film

editing suite which is usable with both 16mm and 35mm optical

sound and magnetic sound film. |

|

|

|

How about Lewis

Gilbert?

Lewis was terrific. He’d come into the cutting room with a glass of wine

and sit down. We had Steenbecks [a flatbed film editing suite] in those

days and we’d just run stuff. And he’d say: “well I don’t like that”, or

”do we have anything else for that?” But as long as the story was working,

he’d leave it to John [Glen] or myself. We had a lot of fun with him in

the cutting room. I saw him not very long ago. He got very involved – one

time when we were watching one sequence, he lent forward and said, “and

that’s where I wanted to go!”, put his glass of wine down and it shot all

over the film. It was very funny. We had to take it all off, dry it and

clean it. That was Lewis. Lovely. A lovely man.

How did it feel when you were offered the role of editor on For Your

Eyes Only?

It seemed like a natural progression but, of course, I was very flattered.

To sit in front of Cubby in the office with all the other heads of

department there and hear him say: “John, how do you feel… would you like

to do the job?” Of course I’d like to do the bloody job! It was a big

responsibility, but I had good assistants and John [Glen] was backing me

up all the time, so it was a very good arrangement – time consuming

though!

What are some of the biggest challenges of working on a Bond film?

What happens on a Bond film is they set the date that it’s going to be

released, and then they say, right, we’re going to release on this date so

if we’re going to shoot by this date, we’ve got to get a script by this

date. But they never had the script ready, or they hadn’t cast it fully in

time, so it always started late! So if shooting ran over, as an editor or

a post-production team we had no period we could over-run! We had to be

ready!

It was the same with Maurice Binder, he had to be ready for the opening of

the film! That became the difficult thing so then you would sometimes need

to take on more people. In that instance [on Octopussy] they called

me supervising editor because we had two or three editors on it, that

helped me out. It was a great learning stage for Peter [Davies] and for

Matthew Glen.

We always had problems with Maurice and the titles. We had one once with

pubic hair in the shot and that had to be taken out! Maurice was a naughty

boy! One Bond premiere I went to – Princess Diana was there – the titles

print arrived that day! I had to go to Rank, cut it in, make sure John was

OK with it and then take it back to London, that was quite frightening!

|

|

|

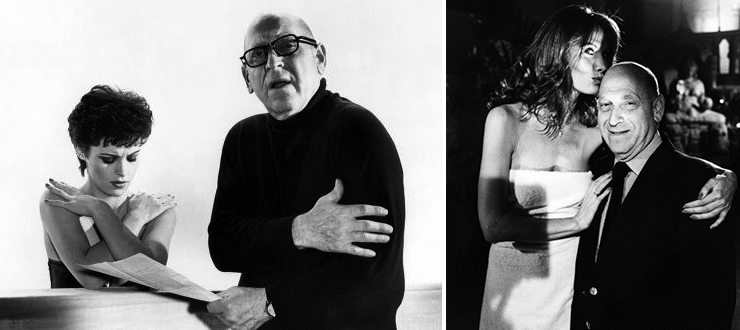

ABOVE: (left)

Maurice Binder filming the For Your Eyes Only (1981) main

title with singer Sheena Easton. (right) Binder with Maud Adams

who starred in Octopussy (1983). Maurice Binder's

provocative opening titles from the James Bond films often got him

into trouble with both censors and editors, due to their risqué

content and last-minute delivery! |

|

|

|

How did it compare

working with Roger Moore and Timothy Dalton?

Loved Roger! Terrific. Absolutely. Such a happy person to be with. If

there was any aggravation anywhere, he’d go out and buy 10 pounds of

sweets and throw them on the set. A terrific guy. I mean I don’t see him

very often but he’s another one who always remembers my name, always takes

the piss out of me! I loved him, and I still do. He was my favourite Bond.

I mean I didn’t work with Sean; I did a lot with Roger and with Tim. Tim

was a good actor but didn’t have a very good sense of humour. You don’t

feel as comfortable with him, he’s his own person. I think that would be

fair to say, but a very good actor. Roger was good at throwaway lines; Tim

wasn’t as good at that as Roger was or Sean was.

Can you explain the role of an editor and what the job involves on a

day-to-day basis?

It’s extremely different today to 20 years ago. A day in the life of a

film editor 20 years ago… For one thing the editor was on the payroll

from either a week before or certainly from the start of a main unit

shooting. He would be responsible with a team. I’d have an assembler, a

first assistant, a second assistant. The second assistant would do the

basic stuff such as synchronising the rushes, because everything was on

film then.

The film would come in from the labs and there’d be a lab report which I

would take to the set. The rushes would come in at about eight in the

morning and the sound would come off at nine or something like that. The

assistant would synchronise the rushes and if it was an action sequence

with a lot of gun shots we’d put a millstone round our necks because we

used to dub the rushes, temp dub them, because if you see a gun shot on

the rushes it just goes, pfft, there’s nothing! So we’d put a real gun

shot in, sometimes we’d put a flash in if the flash didn’t record. We’d do

that because when we ran rushes for Cubby, which was the most important

rushes for us of the day, the presentation, for me, was all important.

Cubby would come into rushes probably at half past 11. There’d always be

about half an hour of rushes, so he’d sit there and hopefully we’d dubbed

it and put some gun shots in.

We didn’t always run the second unit for him, because some of that,

especially with Derek Meddings’ stuff, was all high-speed stuff which

meant there was miles of run-up. We’d try to do that earlier in the

cutting room by taking all that run-up off, but that was very time

consuming and we didn’t often have the time for that. So we’d possibly

send him a selection of stuff to see at another time. |

|

|

ABOVE: (left) The

spectacular pre-credit sequence for The Spy Who Loved Me

(1977) was filmed by editor and second-unit director John Glen on

Baffin Island in Canada, and in Switzerland by ski-chase

co-ordinator Willy Bogner. (top left) Derek Meddings [standing

centre left) on the miniature of the Liparus Supertanker, which

was filmed at high speed when moving in water so that the waves

appeared more realistic when projected at normal speed – this was

a technique Meddings pioneered on the groundbreaking TV puppet

series Thunderbirds (1965-66), which also worked well with

explosions and fire effects. (bottom right) Derek Meddings was

Oscar-nominated for his special effects work on Moonraker

(1979), which again utilised high-speed filming for the model

work, including the destruction of the Drax space station, which

was achieved by firing a shotgun at the large-scale miniature

filmed inside the vast ‘007 Stage’ at Pinewood Studios. |

|

|

|

The next running would be

the crew running in the evening when they’d finished shooting. The artists

didn’t normally come to that, I mean John didn’t like them there because

they would change their performances. But we would try to get make-up and

hairdressing there so that the main unit were looking like the doubles and

the doubles were looking like the main unit, so at least we didn’t have

wardrobe malfunctions and wardrobe that looked wrong. That could go wrong

and did go wrong, on one film we had someone who was meant to have a red

hat on and when it came out of the process it was a blue one!

The rest of the day you’d be assembling stuff. And everything had to be

numbered. Once they’d been synchronised, once everything was in synch, it

would be put on to a machine which would put rubber numbers on it. The

second assistant would then have a logbook and mark down what the numbers

were, and he would also key number it, which is what’s on the film stock

itself, so you knew what was in the laboratories later.

It’s so different today. Completely different. Then the film would be

broken down into small sections of film. Each would be a slate, you know

221 take 1, 2 and 3, you know whatever had got printed. Then I as the

editor I would have marked up my script . I’ve seen the rushes and I’d

marked my script. Sometimes if I was sitting with the director, I’d get a

nudge from John which means that’s the take he likes, or he liked that

bit. So I’d scribble something down and try to slot it in later. That’s

how we communicated.

Then I would put it together. I’d run it on a Moviola, which was a machine

that had a picture screen on the right and a sound head on there. So you’d

have the film coming off my hand. I’d be running it through, feeding it

through. I’d have bits that I liked which I would stop, look at, go

backwards and forwards… It’s difficult to explain! I could show you how to

do it – I could still do it today without any trouble! I’d mark it with

wax pencil where I wanted to start and stop. I’d take it out of there and

go onto a pic synch or a synchroniser and put it in there, so you keep it

in synch. You’ve got the numbers that are on the film and the soundtrack

which holds it in synch, that shows you it’s in synch.

Then you’d just wind it in and join it up with a tape joiner. When I first

started it was with a joiner where you had to do it with acetate and

scrape it and you lost two sprockets, but you didn’t 20 years ago, you

just joined it with a piece of tape. |

|

|

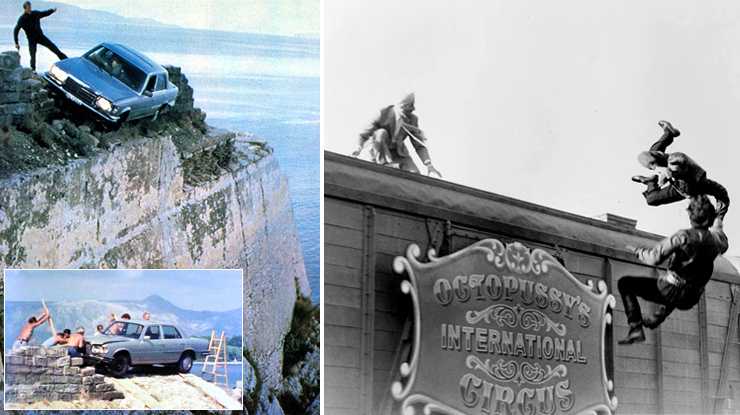

ABOVE: (left) For

Your Eyes Only (1981) One of Roger Moore's standout scenes as

James Bond is his ruthless killing of Locque (Michael Gothard) as

he kicks his car off a cliff in Corfu. The shot was achieved via a

combination of practical action, [inset] brute force, and clever

editing by John Grover and his team. (right) Similar techniques

were used in Octopussy (1983) for the culmination of the

fight on top of a speeding train. Pictured are Stuntmen Reg

Harding (doubling for Kabir Bedi as Gobinda), Paul Weston as James

Bond, and Wayne Michaels doubling Anthony Meyer (Grischka), on

location at the Nene Valley Railway in Cambridgeshire standing in

for West Germany. |

|

|

|

The film would gradually

be built up that way. So you’d have sequences – you’d label a sequence,

say sequence 22, and that would be in a can – well there’d be a can of

picture and a can of sound. So when John came in in the evening or

somebody else wanted to see it or the sound boys wanted to get hold of it,

they would take the sequence out and run it on a Steenbeck because you

didn’t get so much wear on a film that way. And you could go backwards and

forwards and see it in reasonable conditions, not like in a theatre but in

reasonable conditions. And you could stop and start it, and you could wax

it and say that’s incorrect or it’s uncomfortable because it’s jerky or

whatever. Editing is all about trimming and tightening. It’s a hands-on

thing.

If you were waiting for special effects shots, or whatever else, you’d

assemble and put it together and put a piece of blank film with ‘scene

missing’ where the special effects shots were going to go. In the end I

would have them shoot on a rostrum camera either a picture from the

storyboard, so you could then cut the sequence with a little bit of film

of the storyboard so that you could still show it and you could start

timing it.

The Bond films, when I was on them, they all had to be two hours and six

minutes! Ten doubles! You couldn’t go over that! Nowadays they’re shorter

– the last one was too short! To me you haven’t got enough story then.

Peter Hunt laid it all down originally. The philosophy is action, action,

action. It’s all go! Fast cutting. Enough cover so even if you have a slow

dialogue scene it doesn’t seem slow! Americans have an extremely low

attention span! No attention span at all! It must be bang bang! It’s like

MTV – moving wallpaper! But if you’re trying to tell a story you must

balance it… action sequences you can go faster and faster.

I’m not sure if it’s the case now, but on the Bonds the editor was always

taken out on location a week before shooting to set up. On The Living

Daylights I went out even earlier because we had to do playbacks. I

went to Vienna to do music playbacks and set that up. You’d normally start

about a week before although sometimes the film might have shot miles of

stuff before, specialist footage. On Moonraker we’d had

all this stuff shot in Brazil, so there was already a mass of film. And

you’d get the library material if you needed that, back projection shots

and so on. Those are so much better now with green screen and digital

photography. I mean some of the back-projection stuff we had on the Bonds

was awful! I shouldn’t say that, but they were! |

|

|

ABOVE: In addition

to composing the score for The Living Daylights (1987),

John Barry (1933-2011) also appears in the film as the conductor

of the Vienna Orchestra during the World Tour of Kara Milovy (Maryam

d'Abo). John Barry arranged Monty Norman's ‘The James Bond Theme’

for Dr. No (1962) and then went on to compose the music for

eleven James Bond films from 1963 to 1987. |

|

|

|

Did you often have to

delete whole sequences from a final cut of a Bond film?

We rarely lost complete sequences, what we’d often do is make them

shorter. The great thing about John Glen is that, having been an editor,

nothing was ever very long! You never have very many long cuts in a Bond

or long sequences because you can’t cut them. You do enough cover so the

film goes bang, bang, bang – and if a scene’s not working you can cut your

way out of it. Which sometimes can be annoying but sometimes can be a

great blessing, ok cut it there – bang it’s gone!

And your memories of the great John Barry?

I’d been with John Barry on other pictures, so I knew him. We were in

Vienna together for The Living Daylights. I got rather drunk with

John one day, that was Cubby’s fault because they were shooting a big

scene where he was supposed to conduct. It was being lit, it was a big

scene to light, the opera hall or whatever it was. We’d had lunch and

Cubby said to me: “you go and have lunch with John, and chat and look

after him for a while”. His wife had gone shopping I think, with Barbara

[Broccoli]. So they weren’t there. She used to look after him because he

liked his drink! He was a lovely man, very talented. Then John was called

on [set] and he couldn’t stand still! The story is, I don’t know if it’s

true because I wasn’t there, but somebody said that they nailed his shoes

to the floor so that he didn’t move. That’s possible! I don’t know if it’s

true but it’s a lovely story! He was terrific and he could conduct it

whether he was drunk or not!

Normally on a Bond film you’d have a music editor. I would always use

music from other Bond films, and we’d track the picture to it and cut the

picture to it because it creates a good rhythm. With John Barry you’d

leave the music in because most of it was his anyway and he’d use it and

adapt it. His music was very much part of the picture and made it work.

The music drove it.

How closely did you work with Michael G. Wilson & Barbara Broccoli?

The first Bond I was on; Barbara was just a pretty little girl who came on

the set with mum and dad. Michael was always around, and he was basically

a writer and a lawyer. As the pictures went on, they became more and more

involved. Michael would like his little acting bit where he’d get into

each film. Cubby was in one of them too in Venice. Barbara and Michael

aren’t my close friends but if I see them, we talk with no problem at all.

I respect them very much and love the family. |

|

|

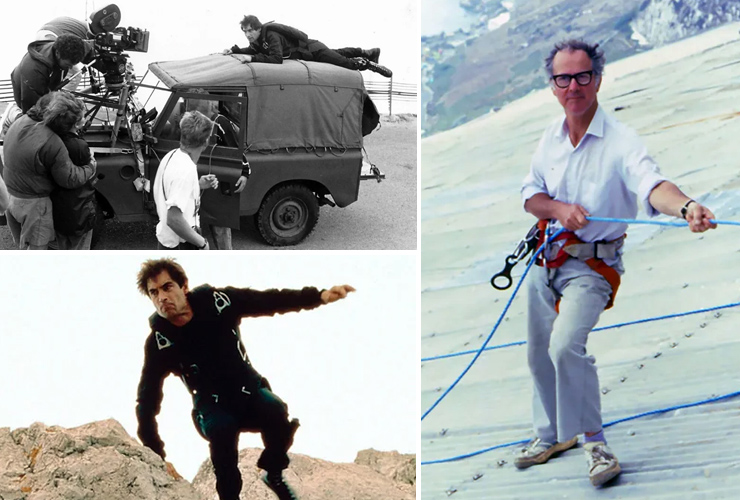

ABOVE: (left) The

Living Daylights (1987) New James Bond Timothy Dalton throws

himself into the action for the pre-credit sequence. (right)

Second unit director Arthur Wooster also gets in on the action in

order to capture the scenes filmed on the Rock of Gibraltar. |

|

|

|

Any other memories of

The Living Daylights?

We had a delay of course. We were going to have Pierce Brosnan as Bond,

and he would have been terrific. We’d done the artist test for him. I

liked him and thought he’d be a terrific Bond. Roger was too old, which

was sad. Tim got the job but unfortunately only did two. Early on we sent

Pete Davies out to Gibraltar – so he was working with the unit. When we

saw the footage back in England the insurers immediately tried to stop it

because Tim was doing the action, which you don’t allow really! He was

very hands-on. It was the start of the picture and he was trying to put

himself out there as a new Bond.

Timothy Dalton’s second Bond film Licence To Kill, was very

controversial in terms of its violence. I imagine that presented you with many

problems. What are your memories of the film and the challenges of editing

it?

They said they’d got to be more violent because all the other films that

were making money were violent. And not quite so much comedy. Tim didn’t

have that sense of humour, if things went wrong, he didn’t burst into

laughter. He was a very serious actor. I thought (that there’d be

censorship problems) I thought my goodness – it’s so graphic! I mean the

body going through the grinder and that sort of thing. Violence on screen

is incredibly easy to shoot, and to show violence off screen it’s got to

be done with sound, for which you need a good sound team, which we had.

We had troubles with the censor, which was a problem because it’s family

entertainment a Bond, and the kids are half the box-office. The censor

made us take a lot out and soften it. Cubby was really upset about that

because of other violent films that were being shown. I mean how did

Spielberg get away with some of his stuff? He got away with murder in the

Indiana Jones films.

When the baddie Robert Davi gets his comeuppance, I mean he deserved it!

He’d killed all these other people, completely ruthlessly! But anyhow, I

went to the censor, and physically re-cut it in front of him, you know

frame by frame. I said: ‘you’ve got to show the guy catching fire

otherwise it doesn’t mean anything!’

In the end it was a compromise and Cubby backed down, I think. We didn’t

have any bad language, but it was violent. With the mechanical shark,

blood and meat, it was rather gory. It was never real sharks, just pretend

ones. It was the blood they were worried about, too much red upsets

people! And of course the noise, the sound was equally responsible for the

violence. That was Vernon Messenger (1928-2026) – blame him for that! The

grinder scene – that was the most violent. And that was violent in the

script, it had all been set up with all the blocks of drugs going through.

That was violent. And it was extremely violent when it was shot because of

all the gore and gunge they shot through, so we did cut most of that out.

But we had to show the threat, what would happen to Bond if he went into

it! They hadn’t had this extreme violence in a Bond film before. I didn’t

think it would disturb children, it might frighten them, but during

Doctor Who for goodness sake, children used to hide behind the settee.

So yes, we set out to make a more violent Bond, which we did. I suppose it

disappointed some of the older Bond people because they wanted us to

continue with the tongue-in-cheek humour, which we didn’t have. The Bond

story was becoming more up to date, not necessarily better but more up to

date. We did a lot of things the censor wanted. There was no terribly

violent sex stuff in it – there was a little bit of titillation but not

very much, there were just beautiful girls for goodness sake! They were

lovely. Carey Lowell was the most beautiful girl you can imagine! |

|

|

What was it like being

in Mexico? Any challenges?

Staying well! The food was okay, but you were always a bit sick, with an

upset tummy or something like that. It was extremely hot; we weren’t

allowed to drive. We had to have a chauffeur car or something because of

the danger. We were in a lovely hotel, but Churubusco Studios were

terribly run down. I think they probably ripped Cubby off… I remember a

lady coming out to paint an enormous backdrop, a huge backdrop, black with

stars, little bits of countryside, this that and the other. It was lovely.

Then Tim was in the boat with Carey Lowell in the romantic scene – it was

done on a big set. I remember how good that painted backdrop was.

What are your memories of the Kenworth truck sequence?

[Second unit director] Arthur Wooster had this enormous storyboard and

huge budget and just presented stuff wonderfully. He was very clever, and

it was very dangerous. How they got the authority to make explosions of

that size I’ll never know! Today you’d have major environmental problems

doing that. You’d do it miniaturised or with CGI, but they were all for

real!

Arthur used to come into the cutting room about once a week. He was at

Cancun, shooting up there and we were in Mexico City. He’d come in and I’d

work for a day with him there so he could see some of the stuff that he’d

done, and some of the stuff that we’d put together. I nicknamed him ‘Which

way Wooster’, because he’d always come in and say: “well, I’m going to

shoot this scene. Which way do you want to shoot it?” And I’d say:

“Arthur, I don’t know, we haven’t got the main unit yet. So I don’t know

if it’s left to right or right to left!” It depended on his storyboards,

but half the time because he had the money, the picture had the money,

they’d do it both ways so we could cut it left to right or right to left.

That’s why the sequence was so good, we had a mass of material. It still

looks good today; I don’t know whether it would be done for real today! |

|

|

What work on

Licence To Kill are you most proud of?

Trying to make the Barrelhead bar-room sequence work… because it was the

first scene to be shot and, to be fair to the director, getting the crew

and all the artists to work together [at the beginning] is difficult. We

made it work in the end but I’m sure John Glen would agree it wasn’t the

best sequence. We had dancers, we had playback, villains, new characters.

It was a difficult scene to light… There were just too many things in

there. It just wasn’t a very good sequence. So to get that to work, I was

proud of that because that’s what an editor’s job is! You’ve got to tell

the story with the material you have. It’s no use saying, if I had a close

shot, I could have done that!

Sometimes on a Bond, if it really didn’t work, if you’re up to date, you

could go and see John and say, it’s really difficult, can you re-shoot

that? And he’d call Arthur in and he’d go and get a close-up and you could

get out of it. That was a privilege that we did have on the Bonds because

we had enough money. That’s also a good thing about having an editor on

location. It’s no use having him back in England and you’re on the other

side of the world!

And of all your Bonds, what was your best work do you think?

Working with Arthur Wooster’s material for the sequence with the train for

Octopussy. The chase. There was so much film to try and sort

through. John and Arthur loved it if you could get everything in that

they’d shot – even if it was just a three-foot cut! So to try to integrate

all this film and have the viewer still follow what’s happening, that’s

one that I was probably most pleased with. It was good – a lot of cuts!

What do you make of the most recent Bond films?

I enjoyed Casino Royale, but I didn’t like Quantum of Solace.

It was completely and utterly over-cut. It destroyed it. I’m sure there

was wonderful material and terrific action stuff, huge amounts of money,

which were destroyed in the cutting room. Although that’s perhaps being

unfair to the editors – the director just wanted to go faster and faster.

But it was not a computer game, it was a film! Watching it, you were

completely lost, if you hadn’t seen the film before you wouldn’t have

known what the hell was happening! No establishing shots, no tension! |